I had just come out of Kent Monkman’s exhibition at the Musée des Beaux Arts de Montréal when it became clear that what distinguishes this work is not critique alone nor reversal but a rare capacity to move fluently across multiple visual cultures and visual civilizations without collapsing them into metaphor. Monkman does not simply cite Western art history and Indigenous visual cultures side by side; he works from within both, mobilizing their internal logics, their modes of authority, and their techniques of address. The result is not hybridity in the decorative sense but a form of visual sovereignty exercised through mastery.

A useful thesis emerges here; Monkman’s paintings function as acts of historical repossession enacted at the level of visual grammar rather than iconography. In other words, his work repossesses history by reconfiguring the rules of representation, not just by changing what is represented. He does not argue against the canon from the outside; he inhabits its most prestigious forms, history painting, baroque theatricality, academic figuration, and dramatic realism, and then reprograms them using Indigenous epistemologies of land, body, and relationality. Indigenous visual traditions are not reduced to symbolic counterweights; they operate as structuring forces that reshape how narrative, space, and temporality behave within the frame.

Monkman’s work is best understood through the idea of medium as a site of governance; the canvas, the museum, the conventions of perspective and realism function as technologies of power, regimes of legibility and perception. These are systems that organize what is visible, what can be apprehended, and what is socially permissible to imagine. Monkman’s intervention is therefore infrastructural; he repurposes the medium itself, demonstrating how forms that once served colonial authority remain operative and can be redeployed to articulate Indigenous sovereignty.

This operation unfolds across multiple scales of attention. In the body, hands and posture carry juridical weight, registering power and consent in ways that recall Caravaggio. Gesture precedes speech, and power is first registered anatomically. A hand resting possessively on a shoulder, a wrist twisted in restraint, a body leaning too far forward or collapsing under its own imbalance; these are not expressive flourishes but signs of command, consent, and coercion. Yet Monkman’s attentiveness extends beyond the gestural into the minutiae of each scene, recalling the densely populated moral ecology of a painter such as Bruegel or Bosch. Small interactions, subtle facial glances, objects in the background, and almost incidental gestures accumulate to form a network of interdependent actions. The paintings do not present a single, legible narrative; they present a field of social relations, a dispersed archive of micro-events.

Landscape functions as a key vector in this operation. The sweeping skies, distant mountains, and panoramic compositions evoke the sublime of Albert Bierstadt and the Hudson River School, yet Monkman retools this language so that land itself becomes legible as contested infrastructure. The horizon is not neutral; it is a site of occupation and resistance. The sublime becomes a device for exposing dispossession rather than producing aesthetic transcendence. In parallel, moments of collective human drama, the twisting, desperate bodies on rafts and in floodwaters, recall early nineteenth-century historical painting. Catastrophe is staged as spectacle, but the audience is made to understand that the spectacle emerges from structural violence rather than narrative fiction.

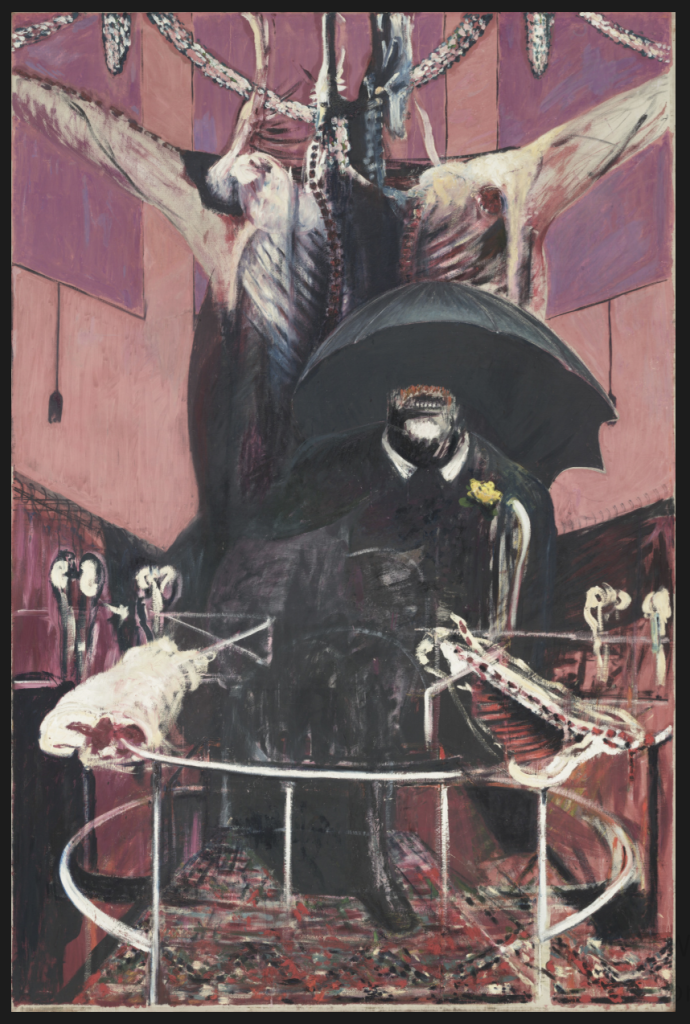

Monkman’s work registers catastrophe in a way that evokes Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa. The raft is not merely a historical reference; it is a pictorial logic of catastrophe as spectacle, a form of mass suffering staged for the gaze. Monkman appropriates this logic but redirects its vector. The suffering is not only a human tragedy but a structural consequence of colonial regimes. Bodies collapse, reach, recoil, and are propelled through space in ways that dramatize structural inequality without reducing the narrative to melodrama. The spectacle remains, but the audience is forced to recognise that the spectacle is not separate from the structure that produces it.

Miss Chief Eagle Testickle moves through these scenes not as a symbol but as a mobile intelligence; her posture is elastic, theatrical, and strategically excessive. She does not correct history; she exposes how history was staged to begin with. In doing so, Monkman reveals the continuity between techniques of Western visual authority and the colonial administration of bodies and land. Indigenous visual traditions intervene not as opposition but as alternative grammars of space, relationality, and temporality, producing a radically polyphonic field of sight.

Seen in Montreal, this matters; the city’s visual inheritance is saturated with Catholic baroque, imperial pageantry, and liberal narratives of tolerance. Monkman’s paintings do not reject this inheritance; they turn it inside out, showing how its techniques remain operative and how easily they can be reactivated. In doing so, the work also reaches back toward the twentieth century, where the surrealist project sought to reveal the unconscious structures that govern perception and desire. Like surrealism, Monkman deploys the logic of the uncanny, but he does so not to escape history or to dissolve the social world into dream, but to expose the way colonial power already contains the irrational, the obscene, and the absurd.

The excess does not produce humour; it produces absurdity, a structural mismatch that refuses relief. The paintings have the precision of historical illusion yet the logic of the dream image, so that the viewer experiences a dissonance between what is visible and what is permissible to see. The viewer is not permitted to laugh and move on; the scene is too precise, too intentional, too materially invested in the power it depicts. The absurdity is not an escape hatch; it is a diagnostic tool that reveals how the colonial order depends on spectacle, fantasy, and the staging of bodies as objects of both desire and control.

This exhibition makes a quiet but forceful claim; that the future of history painting does not lie in moral instruction or archival correction but in the strategic reoccupation of visual systems that once claimed universality. Monkman demonstrates that these systems were never neutral and that they are still available to those who understand them well enough to bend them. By drawing on gesture, minutiae, landscape, and catastrophe alike, he produces a visual language that is both encyclopedic and insubordinate; a sovereign grammar capable of registering the full weight of colonial and Indigenous histories simultaneously while insisting that vision itself is a terrain of power and negotiation.