This essay reflects on François Hartog’s Chronos: The West Confronts Time and Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume to examine how contemporary experience is structured by the density and intensity of the immediate; it considers how algorithms and data operate as instruments of presentism, shaping perception, attention, and ethical judgment, while also exploring the volumetric, spatial, and political dimensions of time that persist as gaps and openings for reflection, action, and the possibility of the event. In practice, this means that even in a world dominated by algorithmic notifications, taking a moment to focus on one’s breath can disrupt the cycle of immediacy, creating space for reflection and ethical choice. This small act of resistance becomes a political statement in an age of temporal commodification

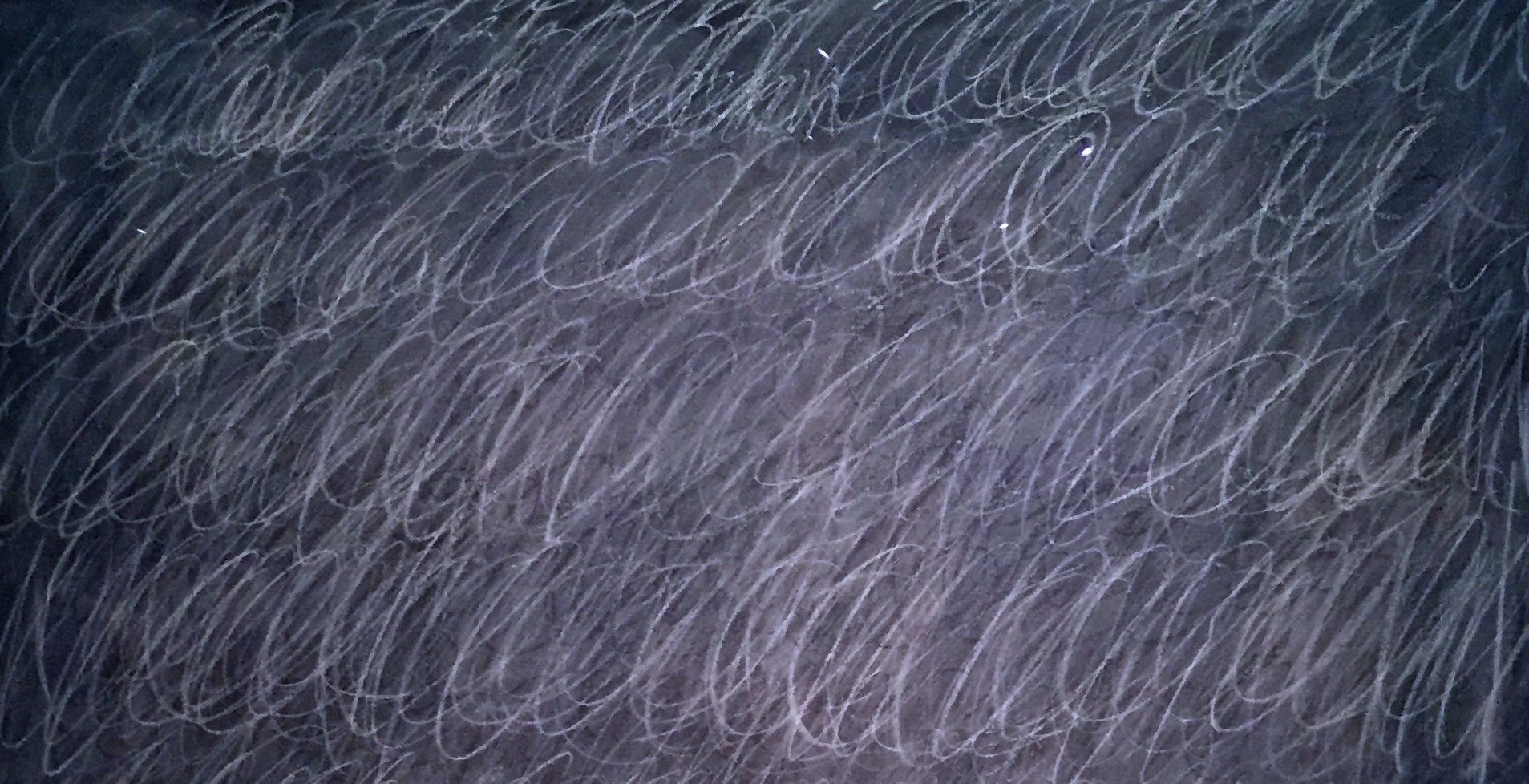

Time no longer flows linearly but weighs, stretches, and bends. François Hartog’s concept of presentism captures this phenomenon with precision: the present thickens into an all-consuming immediacy, while the past is relegated to archives and the future collapses into anticipation and calculation. The now devours perception, enfolds thought, and dictates the very possibility of cognition. Each breath, pause, or glance becomes saturated with urgency, bending attention toward the immediate and away from slow, reflective human thought.

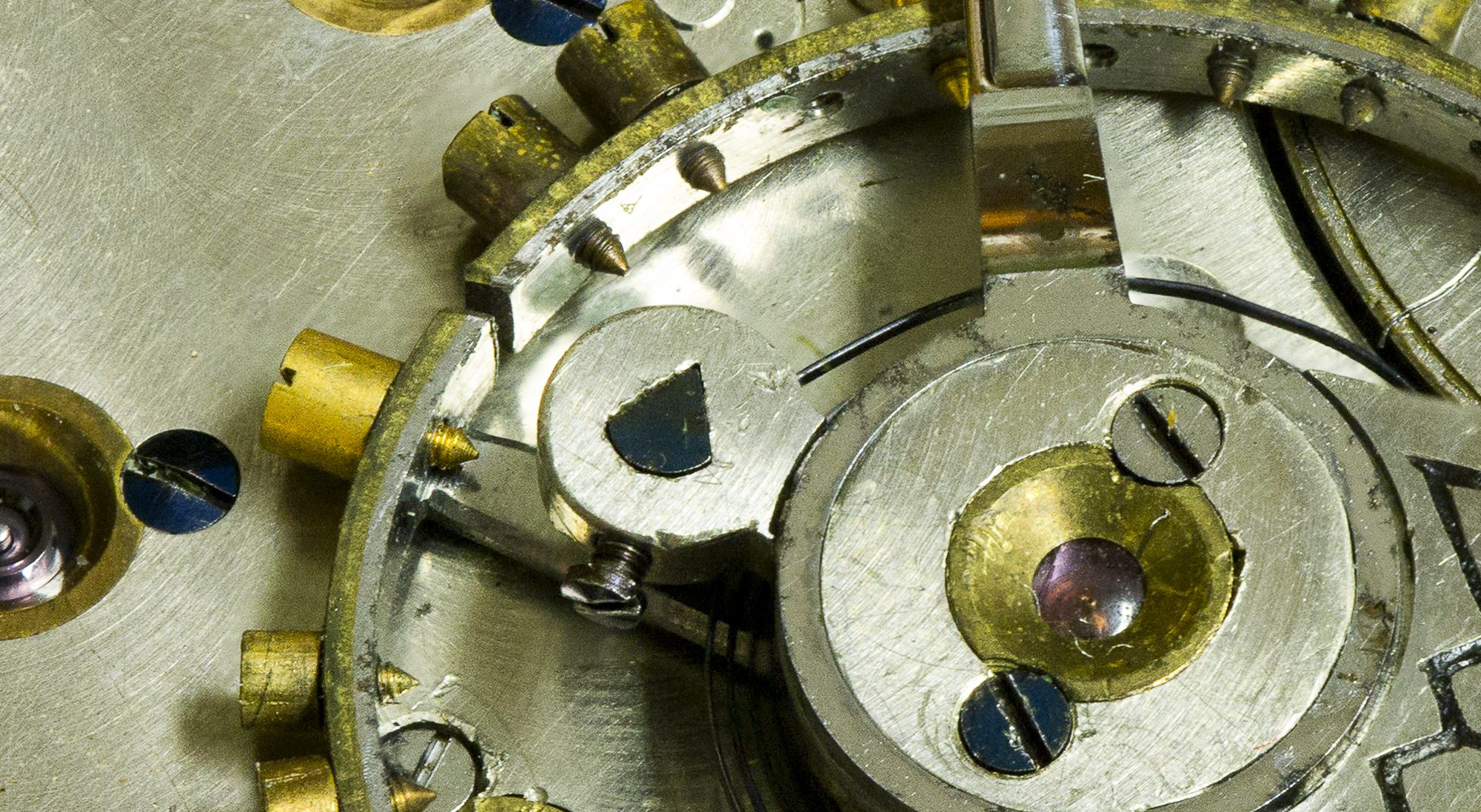

Data and algorithms amplify this temporal pressure. Data provides the raw substrate, capturing traces of action, movement, and behaviour, while algorithms translate these traces into legible, manipulable units. Dashboards, predictive models, and streams of metrics condense the world into fragments of the now, folding them into recursive feedback loops. Algorithms, in this sense, are the teeth of a temporal monster: they bite into the raw presence of data, structuring and presenting the present as both comprehensible and overwhelming. Immediacy thickens, intensifies, and hollows out slow time, leaving human rhythms—the time of the breath—fragmented and compromised. The phenomenology of data is enacted through algorithmic mediation; it is only through algorithms that data becomes perceptible, shaping attention, memory, and perception itself.

The seduction of this system is both perceptual and political. Predictive algorithms, real-time analytics, and constant monitoring promise mastery, optimization, and control. Yet their scale, complexity, and opacity render such mastery provisional. Governments, corporations, and institutions deploy these tools to regulate behaviour, anticipate risk, and shape populations. The temporal density of the present becomes a political instrument, codifying attention, compressing reflection, and normalizing immediacy. Here, density refers to the accumulation of temporal moments, the layered presence of events, while intensity captures the pressure and urgency that these moments exert on perception and cognition; algorithms manipulate both, structuring the present to maximize immediacy while hollowing out slow, reflective time. Data flows through algorithms, structuring perception while reinforcing power, embedding the devouring present into everyday experience. This is more than capitalism; it is the monetization of time itself, a system where every moment, every breath, every micro-attention is reduced to a measurable increment, stripped of meaning except as a unit to be processed and consumed. Beyond the standing reserve of things, this is a standing reserve of the present, where experience, reflection, and ethical possibility are harvested, quantified, and compressed, leaving only the illusion of control.

To inhabit this mediated present requires rhythm, attention, and awareness lest you get lost in the Heraclitean torrent of the now. Notice the cadence of notifications, alerts, and feeds—the pulse of algorithmic time pressing on thought. Feel the compression of attention into micro-increments, the folding of past traces, projected futures, and quantified nows into each gesture. Presentism is enacted in every swipe, every calculated anticipation. Yet spaces remain for reflection, ethical judgment, and bodily presence. Awareness of the structures governing perception allows one to inhabit the present without surrendering entirely, tracing micro-rhythms and perceiving folds, gaps, and intensities that slip beyond measurement, beyond data, beyond algorithms.

The body measures temporal density through breath, heartbeat, and subtle gestures—rhythms that defy calculation. A pause, a deep inhalation, or a moment of stillness expands the present and slows its intensity. Pranayama, an ancient yogic breathing practice, can be seen not just as a spiritual exercise but as a way to experience time itself—a ‘phenomenology of time’ that reveals its texture and rhythm; it transforms breath into a form of knowledge, where rhythm and pause disclose temporality as irreducible to data and uncapturable by the algorithm. In this sense it resonates with Hannah Arendt’s description of the “gap” between past and future, that interval where thinking becomes possible, and with Christine Ross’s exploration of the temporal event in contemporary art, wherein moments can rupture habitual patterns and open new possibilities for perception and action. By grounding the abstract concept of time in bodily experience, pranayama reveals how lived time—thick, slow, and attentive—resists the urgency imposed by data and algorithms. This somatic approach aligns with Arendt’s notion of the ‘gap’ between past and future, where ethical thinking becomes possible. Perceptual vigilance, ethical attention, and recognition of temporal folds become acts of resistance, ways of dwelling in a dense, intense now without being consumed by it.

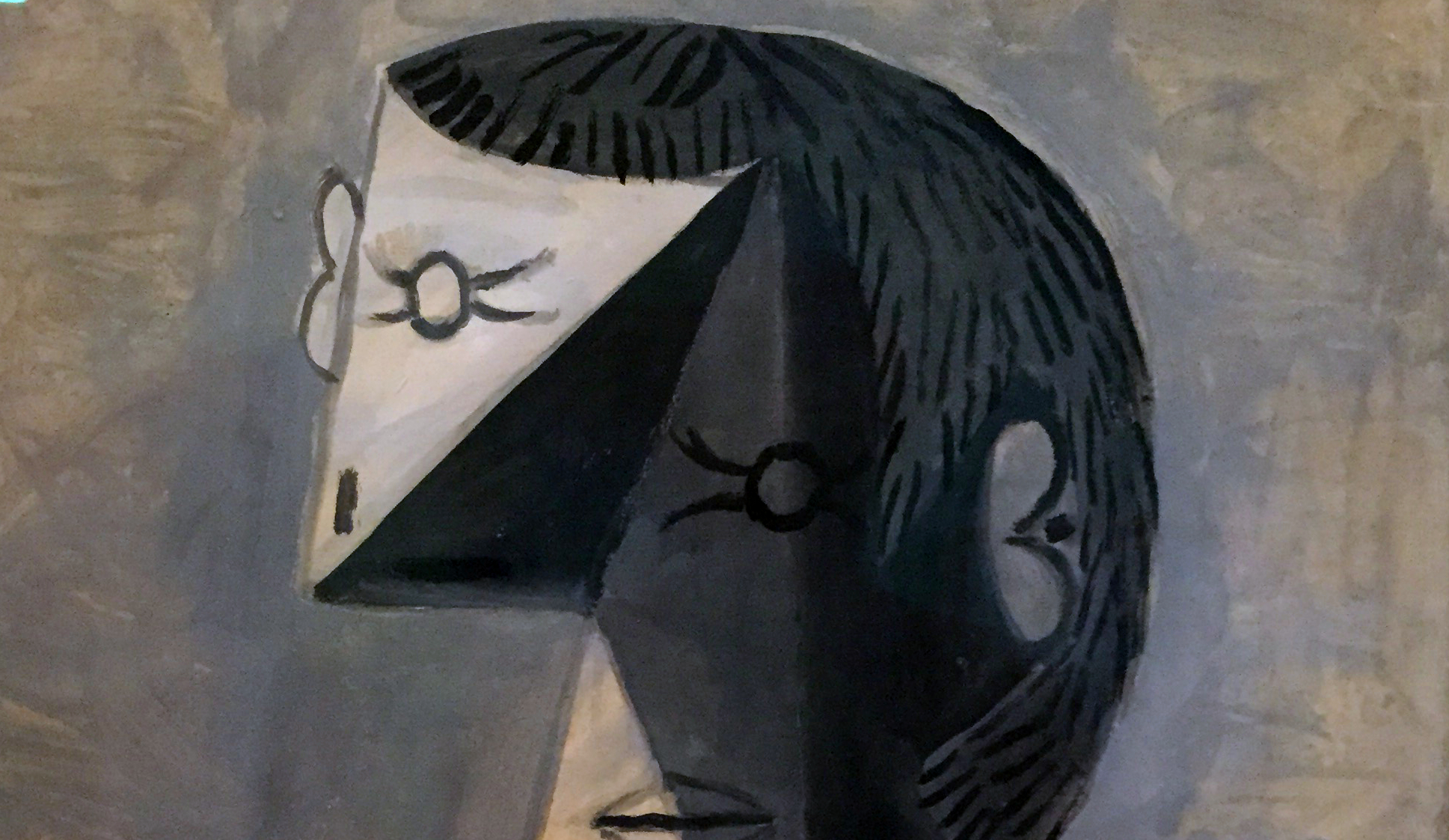

On the Calculation of Volume offers a frame for this intensity. Each fragment of the present is volumetric, measurable yet interconnected, dense yet permeable. The now is a field of relational magnitudes, where every action, data trace, and algorithmic operation contributes to a totality in flux. Time’s volumetric density, akin to matter in space-time, exerts pressure on perception and ethics, accumulating yet remaining fluid.

Drawing on Sloterdijk’s philosophy of ‘spheres and foam,’ the present can be imagined as a bubble within a larger, porous network. Each bubble is a bounded yet interconnected space—individual yet inseparable from its surroundings, much like cells in a living organism. Algorithms carve into these spheres, structuring, intensifying, and documenting them, but the foam’s porosity ensures that no total mastery is possible. These spheres are inhabited spaces of reflection, political judgment, and ethical action; their relationality allows for rupture, contingency, and the emergence of events beyond calculation. In this sense, each volumetric present is both mediated and immediate, enclosed yet open, a site where density and intensity, pressure and accumulation, coexist and interact.

Breath, pause, perception—the present unfolds in thickness, intensity, and relationality. Yet within this density remain gaps, spaces of suspension, as Arendt reminds us, where attention and judgment can surface, where ethical and political choice can intervene. These gaps resist full capture by metrics, algorithms, or the teeth of the temporal monster. Christine Ross’s reflections on the possibility of the event extend this insight: even within a heavily mediated, algorithmically quantified present, occurrences can emerge that exceed calculation, rupture expectation, and open new temporal trajectories. The devouring now is not total with the space of Augmented Reality, for example; within its folds persist spaces for surprise, reflection, and action. One inhabits it not in mastery but in careful attentiveness, navigating between density and openness, intensity and gap, algorithmic imposition and the possibility of the event. Data flows through these structures, producing both pressure and opportunity.

Time presses, bites, enfolds, and in its volumetric density, in its temporality, there is room to dwell, act, and breathe. Hartog’s analysis illuminates the contemporary condition: data and algorithms codify, structure, and circulate the devouring present, giving it density, rhythm, and shape, while promising comprehension that is always provisional, only now. The political stakes are immediate; these instruments organize populations, regulate attention, shape behaviour, and mediate social norms, from predictive policing to real-time financial analytics. To dwell in this Age is to inhabit a temporal field that is both structured and wild, dense yet ephemeral, bounded yet permeable; density accumulates moments, intensity exerts pressure on perception and action. The teeth of the temporal monster bite, constrain, and create the illusion of control, yet within these imprints remain spaces to perceive, attend, act, and judge. The present is not a point to control but a dynamic, ethically charged field to inhabit. By navigating its intensity and density, we resist the illusion of total comprehension and reclaim time as a space for reflection, action, and freedom. It becomes a series of inhabited spheres, measurable, mediated, and experienced, where data and algorithms document, structure, and intensify pressure without exhausting the lived, political, or ethical possibilities of the moment.

See Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future, 1961. "The gap between past and future, which is the space of thinking, is the space in which freedom can be experienced."

See Peter Sloterdijk, You Must Change Your Life, 2013 - English translation."With a concept of practice based on a broad anthropological foundation, we finally have the right instrument to overcome the gap, supposedly unbridgeable by methodological means, between biological and cultural phenomena of immunity–that is, between natural processes on the one hand and actions on the other." I will note his thinking is dense. It took me 2.5 years to finish his three part Magnus Opus: Spheres and I don't think I have even scratched the surface of it.