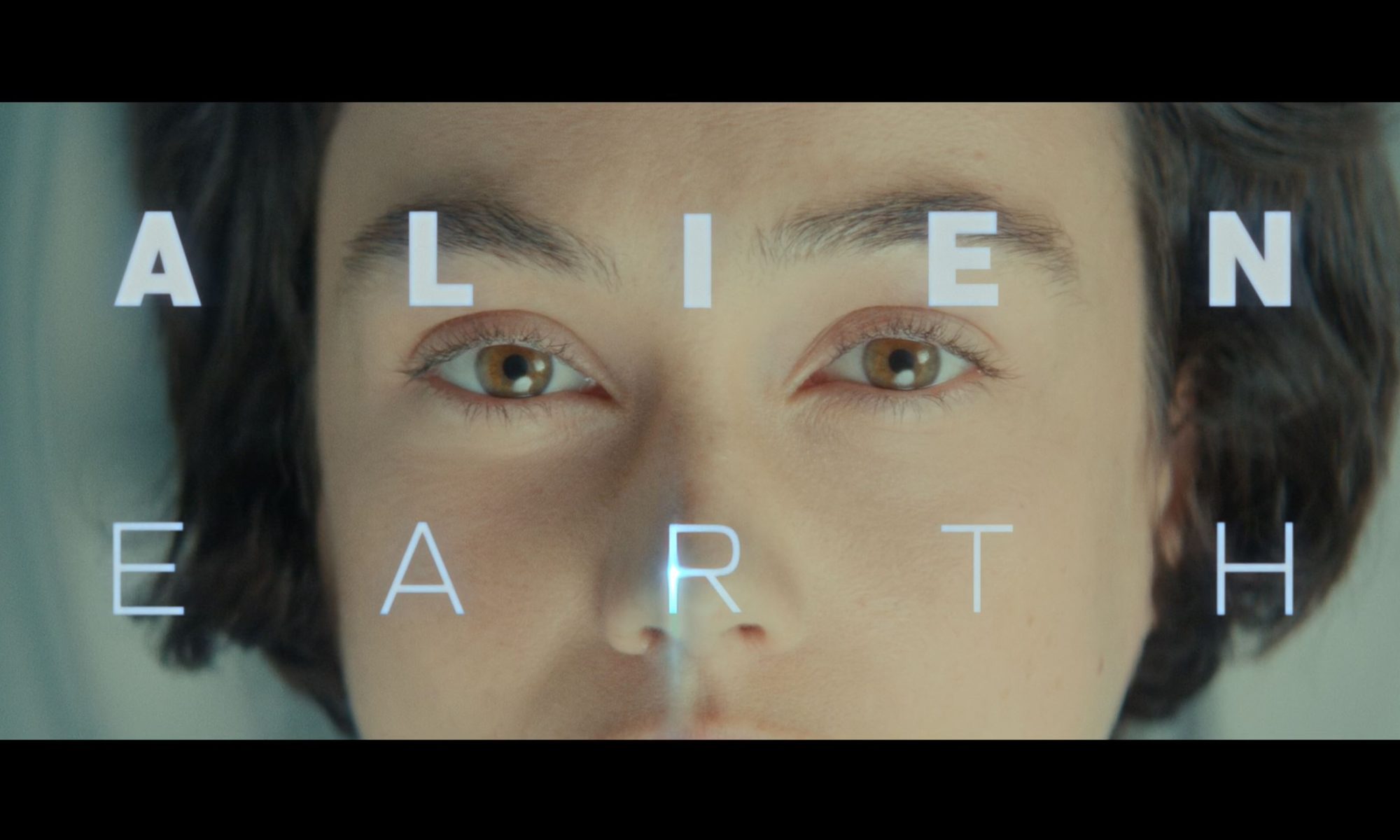

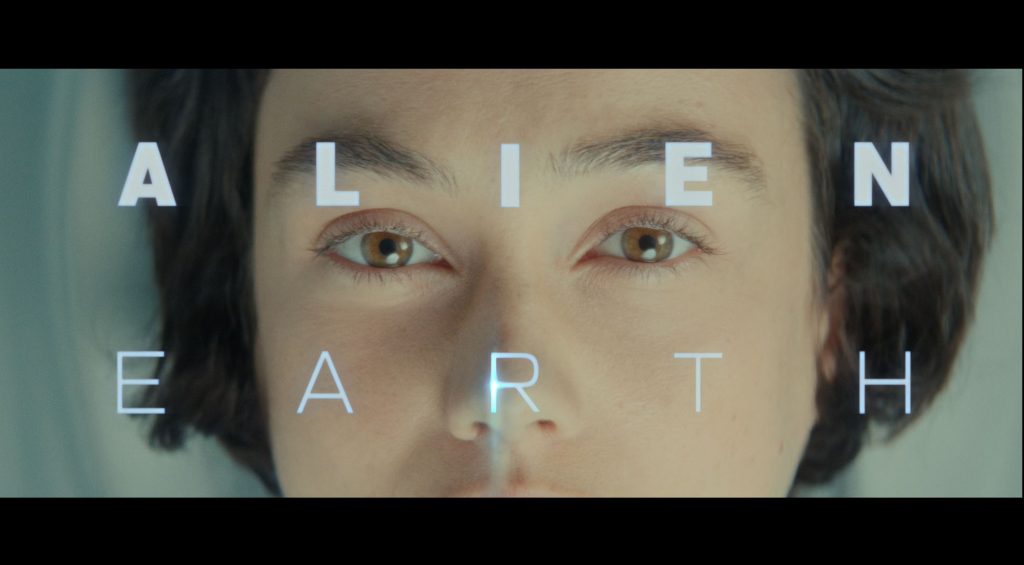

I just started watching Pluribus, and after three episodes, the show certainly is thought-provoking. An alien virus has made everyone around Carol Sturka perfectly happy, while she alone remains immune, exposing the absurdities of this artificially cheerful world. Like Gilligan’s earlier work and contemporary series such as White Lotus and Severance, Pluribus explores the ethics of abundance, showing how privilege and surplus can constrain perception, alienate consciousness, and reveal the limits of happiness itself. I don't think there are any spoilers below but buyer beware.

Vince Gilligan’s Pluribus emerges as a contemporary meditation on privilege, consciousness, and the paradoxical consequences of abundance. The series situates its protagonist, Carol Sturka, within a world of totalized plenitude, where an alien virus has imposed universal happiness, rendering conflict, frustration, and desire largely obsolete. Unlike Gilligan’s earlier work, where scarcity and ambition catalyze moral compromise, Pluribus stages a reversal: surplus itself generates existential tension and ethical exposure. The series’ formal and narrative ingenuity lies in this inversion; it posits that discontent is not merely a social or economic condition but an ontological necessity, essential to reflective consciousness and moral agency. Carol’s immunity to the hive-mind functions as the narrative fulcrum; her solitude enables her to perceive the absurdity of a world insulated from struggle and to enact critique through both observation and the meta-narrative of her authorship. Her vocation as a novelist within the series underscores the persistence of narrative as a medium for ethical and imaginative engagement, suggesting that even in an artificially harmonious society, reflection and moral discernment remain contingent upon the recognition of deficiency. For instance, when Carol observes neighbours engaged in superficially perfect domestic routines, their automated cheer and polite courtesy highlight the emptiness beneath their compliance; her marginality allows her to read these gestures as performative rather than authentic, echoing Gilligan’s interest in the moral visibility of character seen in Breaking Bad.

This exploration resonates strongly with another contemporary media offering: White Lotus, which similarly interrogates the vacuity and moral precarity of affluence, though it does so within a realist-comic register; for example, the tension between the wealthy resort guests and the staff exposes ethical blind spots, hypocrisy, and narcissism that parallel the hive-mind’s elimination of struggle in Pluribus. Whereas White Lotus relies upon character-driven friction and social satire, Pluribus employs speculative exaggeration to render the consequences of privilege both literal and philosophical; the virus functions as a structural amplification of the dynamics evident in the resort’s gilded microcosm, revealing how material plenitude can obscure ethical and emotional perception. Carol’s discontent functions as a critical mirror to the hive-mind, much as observational narration in White Lotus illuminates the foibles and insecurities of the wealthy; in each case, surplus does not generate freedom but exposes constraints on awareness and moral reflection.

This convergence of spectacle and structure reveals a shared concern with the architecture of insulation itself. Both White Lotus and Pluribus dramatize environments in which systems of comfort have assembled into invisible prisons, yet they differ crucially in their treatment of complicity. Where White Lotus stages privilege as a social performance requiring active maintenance (guests must continually rationalize, deflect, and perform their entitlement), Pluribus presents it as involuntary absorption, a condition imposed rather than chosen. This distinction illuminates a central anxiety in contemporary narrative: whether ethical failure stems from willful blindness or structural determination. Carol’s immunity renders her uniquely capable of witnessing both dimensions; she observes a society that has automated the very self-deceptions White Lotus‘s guests labour to sustain. The hive-mind represents the logical terminus of privilege; it produces a state in which ethical compromise requires no effort because ethical consciousness itself has been eliminated. Yet if White Lotus suggests that wealth corrodes moral perception through gradual habituation, Pluribus asks a more unsettling question: what remains of agency when happiness is no longer a pursuit but an imposition? This query finds its most acute articulation in Severance, where the mechanics of division literalize the psychic fragmentation latent in both earlier works.

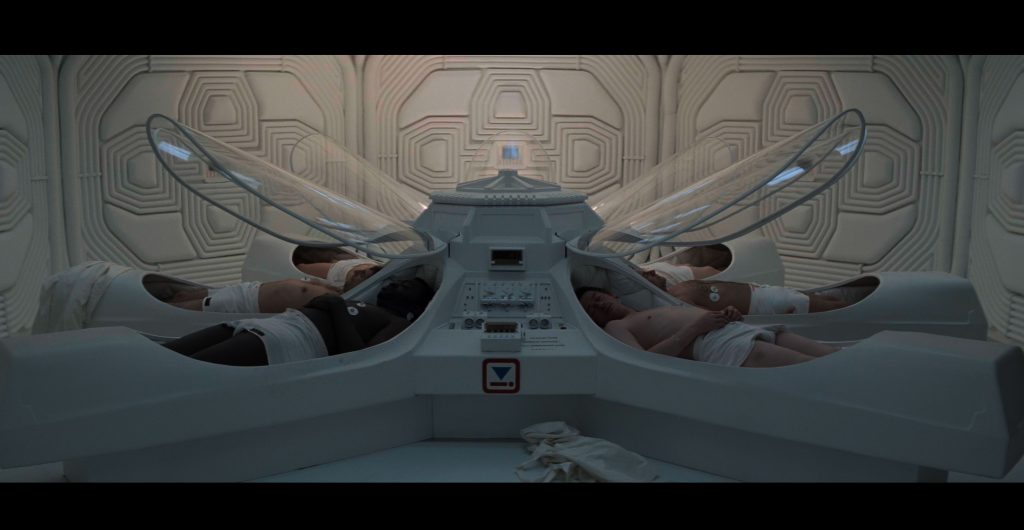

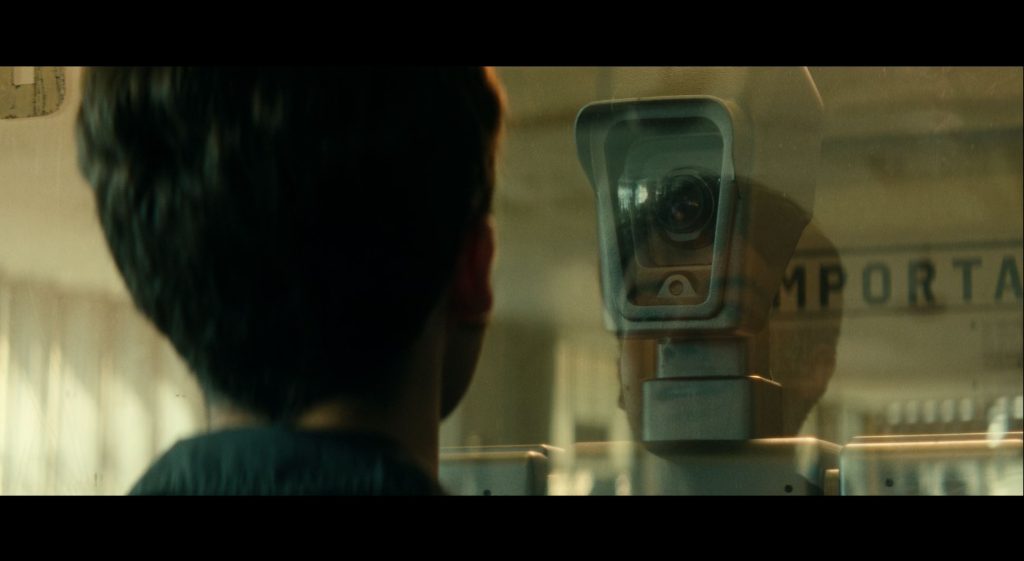

Severance offers a further parallel in its exploration of alienation induced by structural and technological intervention; the bifurcation of work and personal consciousness mirrors the hive-mind of Pluribus, producing environments in which experience is regulated and perception constrained. The early scenes in Lumon Industries, in which employees operate under divided consciousness, echo Carol’s isolation: both narratives dramatize the cognitive and ethical consequences of insulation from the full spectrum of human experience. Both series suggest that ethical and existential reflection arises from disruption; in Pluribus, Carol’s immunity creates the friction necessary for perception, whereas in Severance, the narrative tension emerges from the impossibility of total integration. In each case, discontent and awareness are inseparable, demonstrating that narrative and moral agency require conditions of insufficiency or limitation, even within worlds engineered for optimization and contentment.

Taken together, these works reveal a contemporary preoccupation with the paradoxical consequences of abundance; wealth, comfort, and structural optimization do not guarantee moral clarity or emotional fulfillment but frequently amplify alienation, narcissism, and ethical fragility. This shared concern marks a departure from earlier interrogations of privilege, which tended to focus on the mechanisms of acquisition or the violence required to sustain advantage. Instead, Pluribus, White Lotus, and Severance direct their attention to the afterlife of privilege: the psychic and moral conditions produced when comfort becomes totalizing. Pluribus extends Gilligan’s longstanding interest in character under pressure into a speculative register, literalizing the effects of privilege and happiness as externalized conditions rather than internal compromises. Where Walter White’s descent required accumulating choices and moral erosions, Carol’s predicament is imposed from without; she suffers not from what she has done but from what has been done to her world. Her suffering is not simply an individual deficit but a diagnostic lens, revealing the limitations imposed by a world in which friction, conflict, and scarcity have been removed. The work thus inverts the logic of Gilligan’s earlier achievement: if Breaking Bad demonstrated how scarcity and ambition corrupt, Pluribus reveals how surplus and satisfaction anesthetize.

The series’ alignment with White Lotus and Severance situates it within a broader aesthetic discourse in which contemporary anxiety about wealth, control, and social engineering is interrogated through narrative form, characterological depth, and speculative exaggeration. Yet Pluribus occupies a distinct position within this discourse; it combines White Lotus‘s satirical acuity with Severance‘s speculative architecture, producing a hybrid form that is simultaneously comic, philosophical, and dystopian. Carol’s authorial vocation becomes crucial here; as a novelist within the narrative, she performs the very act of critical observation that the work itself enacts. Her writing functions as resistance, a refusal to accept the hive-mind’s foreclosure of narrative complexity and moral ambiguity. In this sense, Pluribus is not merely about the dangers of imposed happiness but about the necessity of narrative itself as a mode of ethical engagement. The work suggests that storytelling requires discord; without conflict, there can be no plot, no character development, no meaningful choice. Carol’s immunity preserves not only her consciousness but her capacity to generate narrative, to transform experience into reflection.

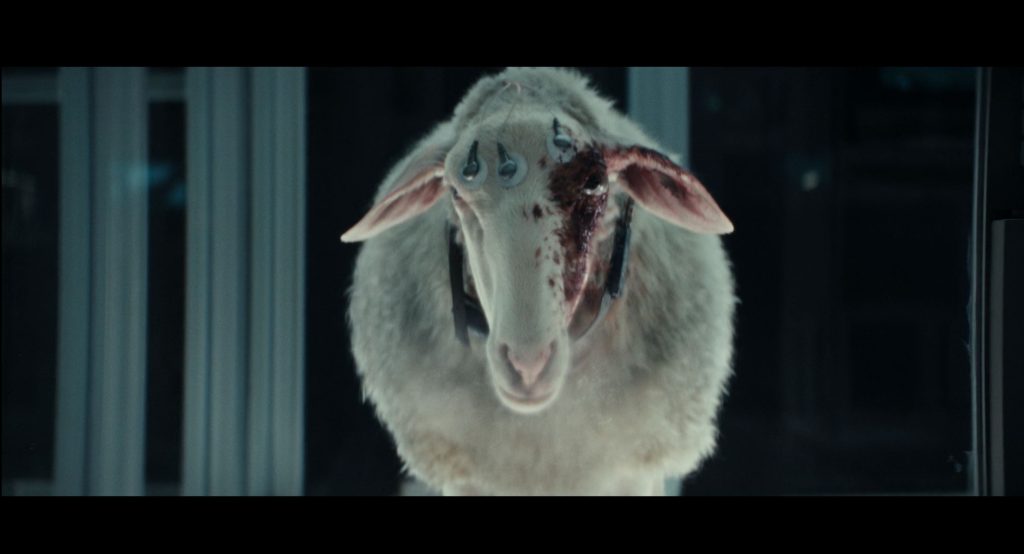

Carol's immunity positions her as a failed node, a processor that refuses synchronization with the network. This technological allusion underscores the series' concern with systems engineering applied to consciousness itself, suggesting that the hive-mind represents not natural evolution but an imposed architecture of connectivity that sacrifices autonomy for seamless integration.

Ultimately, Pluribus functions as both philosophical inquiry and literary artifact, dramatizing the necessity of discontent for consciousness and moral judgment. By centring a protagonist immune to artificially imposed happiness, Gilligan stages a meditation on the enduring value of imperfection and the ethical imperative of observation. The series reveals what White Lotus and Severance also demonstrate: that contemporary anxieties about wealth, control, and social engineering find their most incisive expression through narrative speculation. Where White Lotus exposes the vacuity beneath privilege through guests’ frustrated desires, and Severance reveals how structural division constrains ethical awareness, Pluribus literalizes these dynamics through its alien virus, rendering metaphorical conditions concrete. Together, these works suggest that the most profound human tensions and imaginative possibilities emerge not from deprivation alone, but from the recognition of what abundance obscures. Privilege does not merely corrupt; it blinds, narrows, and flattens the texture of experience until existence becomes indistinguishable from performance. In a world engineered for contentment, Carol’s suffering becomes diagnostic: it reveals that meaning, agency, and moral clarity require precisely the friction that privilege seeks to eliminate. Her pain is not pathology but lucidity; her isolation is not exile but the necessary distance from which critique becomes possible. The work thus moves not toward resolution but toward affirmation: that consciousness, narrative, and ethical life depend upon the preservation of discomfort, the refusal of totalized harmony, and the recognition that human flourishing requires not the absence of struggle but its meaningful presence.