Amidst all the other things going on I was pleased to spend time at the National Gallery yesterday. The new exhibition featured some exceptional works of arts from a range of Canadian artists from Emily Carr to James Wilson Morrice. A catalog was produced and, as usual, it is a well produced book with nicely coloured plates and good paper for viewing them. I will go several times to the exhibit after reviewing the catalogue and reading the essays.

For now my head is brimming with questions such as how these artists thought about impressionism and their pictured responses – and would the artists assembled in this collection think of themselves as impressionists, whatever that might have meant to each of them? The catalogue and its essays will help me understand this better from a curatorial and academic perspective. I am cognizant of the use of the term “impressionism” and how it was originally a satirical take on what once critic assumed was an “unfinished work”.

I take this as my starting point: as the camera aesthetic emerged as a means of visualization and “freezing time” (think Muybridge) and “documenting” time (think of the use of the camera for policing and anthropological itemization), imaginative works of paint were not limited by the “instant” nature of time and could allow interactive lighting effects between the viewer and the object of art to mimic time but non-synchronically.

As an aside I find that I need a multi-media or a multi-modal perspective, not a “virtual collage” but rather an assemblage of techniques and tools to reflect upon. Since each medium* has its own “perspective” and each has their own benefits, when I approach objects like this exhibition I want to create my own first impression before I consume too much of other people’s perspectives and biases accrete. Much like how I normally don’t like to listen to the audio guides the first time: I prefer to take my time and explore on my own initially. This is an entitled view, of course, since I can visit this Gallery frequently.

*Marshall McLuhan has been on my reading list of late. I have recently found a copy of the first article that I ever wrote on the internet back in the 1990s on McLuhan, filled with my embarrassingly youthful utopian ideals about the global village and its hope.

My interest in Impressionism is its treatment of light. I see this predominately in relation to the emergence of photographic tools and aesthetics and how these challenges were faced by painters.

Of course by the time I saw the first work at the Gallery, it was the colouring that most grabbed my attention. And notwithstanding some lighting issues in several of the rooms (since these rooms were designed for prints and not framed canvas works) with shadows that interfered with the artists composition (the Carr landscape has its yellow sky darkened), the works are a cornucopia of styles and techniques that provided several hours of viewing pleasure. The application of paint and its control was intriguing like this example, from Ernest Lawson’s Canal Scene in Winter.

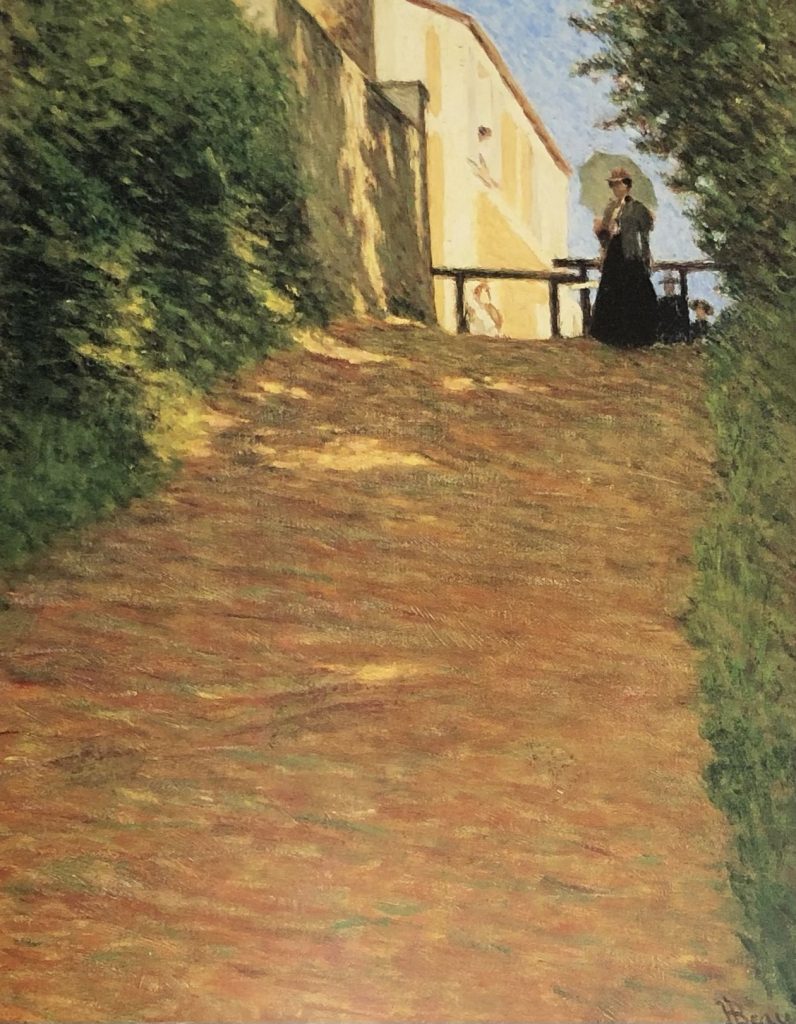

I have been reading the essays from the catalogue and am struck by a remark that artists such as Maurice Cullen shared certain attributes with Hokusai. It struck a cord with me since I have shared that opinion not only of Cullen but that many works of easel paintings of landscapes from the mid-19th century share not just the colouring and loose brushwork but also that same “angle of view” that resembles an aerial perspective or a hilltop view as opposed to a eye-line frontal viewing perspective. Visualization in late Meiji (called “modernizing” Japan in the West) Japan shares many of these elements. This presages the aerial views that were popularized by painted visualizations from hilltops, tall buildings, airplanes or balloons in the early 20th century. I think of it as an “anthropological” perspective. It differs for me from a “cartographic” perspective used by the Dutch in Elizabeth Sutton’s work, for example. It assumes an objective rather than a notational perspective. It is this assumption of “objective” that is soon to be the subject of much attention in the first half of the 20th century.

The artist and the viewer have a larger focal length and more encompassing view that someone that would be a participant in the visual would have; not necessarily omnipotent but detached. So while the more “standard” impressionist work from the urban streets of Paris were photographic, many took the imagined perspective from slightly above. Note the Harris below compared with the Milne. Also, its opposite in the Henri Beau.

And my three favourite works from this visit are below. I cannot help but make the connection between the urban and industrial works and Burtynsky’s photographs in his Anthropocene.