And some art by Caravaggio and Michelangelo.

Canada and Immigrants from Europe post 1945

The Canadian government was recently vilified for the appearance and recognition in Parliament of an immigrant from Ukraine who served in the Galicia Division that was formed in 1943, made up of Ukrainian volunteers to fight against the Soviet Union. I decided to look into the text of the 1985-1986 Deschênes Commission that was digitized in 2012 by Privy Council Office to educate myself on this issue. This Commission was established specifically to report on the issue of war criminals in Canada and included discussion of this specific movement. Text is provided for Part I that was designed to be published with Part II, destined to remain confidential although there are calls to have this released. The number of war criminals in Canada ranged from a “handful” to 6000 at the time of the Commission. It should be noted that outside interveners in this Commission never quoted a figure under 1000.

The Report shows the geo-political role played by Canada at the end of the War in Europe, suffering immensely due to the economic collapse of decades of hostilities and war. All Europe was now moving, in one direction or another, and Canada’s economic goals aligned with geo-political goals of managing the recovery of Europe through the acceptance of large numbers of persons displaced by war, even if many of these policies originated in Washington or London. The Report also shows the limitations of Canadian authority as it emerged from its subordinate Dominion status. The accoutrements of a mature state were not yet in place.

As a (barely) former colony of the British Crown, Canada only enacted an independent Immigration Act in 1952 and decisions made by Cabinet in this instance must be considered using this lens. Independent foreign policy was less than two decades old at the close of hostilities. Immigration was subsumed under Order in Council P.C. 1931-695, a tightly restrictive policy. The Citizenship Act of 1947 was a step away from Canada’s status as dependent but a “Canadian” immigration act was still years away. Immigration was controlled from the centre, as it was in 1919, policies put in place after the Great War.

I’ll also add that since Canada was not a signatory to the Charter or the 1945 London Agreement, it didn’t have any jurisdiction over this type of offence. Canada still did not have fully developed State authority over elements that would have been needed here. This was only to come over the next decade. As the report makes clear, there was no attempt to hide the fact that these persons were members of the German military that Canada was at war with so no basis to claim that these people hid their histories and overturn their status in Canada.

Canada began to play a key role in the emergent Cold War of the late 1940s as a “release valve” for emigrants from across Europe, including those who lived in former Nazi and fascist controlled areas across Europe. Immigrants from all over the continent wanted to immigrate out of Europe, many of them living years directly or indirectly under fascist rule, suffering oppression and genocide. The initial years of the post-war were dedicated to returning Canadian service personnel from across the globe. Immigration as we know it was non-existent and “who” could immigrate was moot. As order returned, so too did the desire to manage this migration for state goals. Demand was coming both from our allies in Europe and the US, along with Canadians who wanted their family members to join them here, not to mention economic growth. Economic growth as a key policy priority was evident in the 1947 agreement with the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Agency and the International Refugee Organization to bring people from Europe as contract workers in specific labour markets.

In June 1949 all immigration was restricted by Order in Council 2743 to those with relatives in Canada, citizens of the UK, USA, and France and agriculturalists, miners, lumberers, loggers and domestic workers. These occupations did not, of course, have Occupational Codes since no system such as the National Occupational Classification or any occupational codes were in place. This data was not to be collected for decades. But I digress. Important for us here is that the Canadian government had denied the entrance of Ukrainians currently held in the UK including the Galicia / Halychyna Division.

This Ukrainian division had surrendered to British forces in May 1945 and were held in Rimini until 1946 when they were screened and transferred to the UK. After the repeal of P.C. 2743 in 1950 by P.C. 2856 there was a change in policy to accept, among others, this group that was currently held in the UK noting that they still required screening both for the immigrant and the applicant in Canada, if applicable. The Canadian Jewish Congress objected and Ottawa paused.

The British Foreign Office stated that both Soviet and British missions had no evidence that these persons fought against Western Allies or engaged in crimes against humanity. And while the CJC continued its objection, Canada opened the doors to Ukrainian immigration from the UK. According to the Deschênes Commission, approximately 600 of these former members of the Galicia Division were in Canada in the mid 1980s. Simon Wiesenthal gave a list of 217 specific names to then Solicitor General Robert Kaplan. This list was investigated and of those, over 86% never set foot in Canada and the few that did had no specific accusations leveled against them. Investigations by both the RCMP and the Commission reached the same conclusion.

I invite you to read the report. It is an interesting story of immigration to Canada that reaches into our own day with the resignation of the Speaker of the House last month.

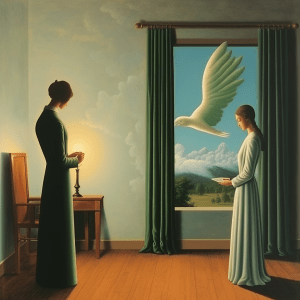

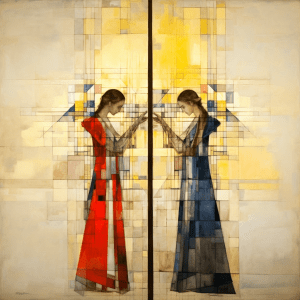

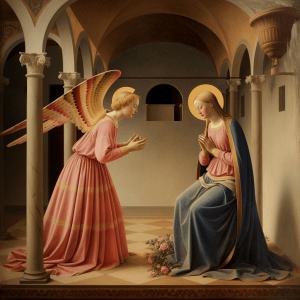

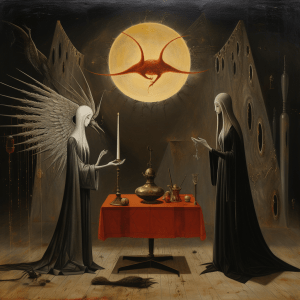

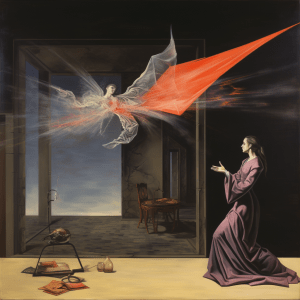

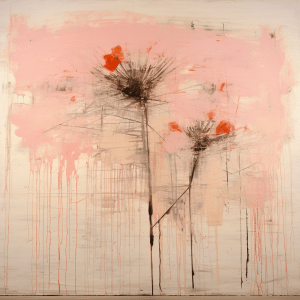

MidJourney and the Annunciation form

I have been experimenting with standard forms in Catholic art from the 13th to the 16th century. Here are some midJourney examples.

Rene Magritte, de Kooning and Cy Twombly on the top row, Modigliani, da Vinci and Philip Guston on the bottom.

Basquiat, Piet Mondrian and Jasper Johns.

Agnes Martin, another Basquiat, Lucian Freud, Fra Angelico and Leonara Carrington.

Klimt, Picasso, Egon Schiele, Francis Bacon, Cy Twombly and Banksy.

Bierstadt and American Exceptionalism

My artist friend John is sending me various artists or movements or subject and style that I am using to picture in midJourney. For me I get the chance to experiment and to learn about each of these artists since I was finding that I was repeating a lot of prompts so needed some inspiration. In this case he wanted a “seascape by Albert Bierstadt” (1830-1902), Prussian born and part of the Hudson River and the Rocky Mountain schools of American art.

As I was reading up on him and the subject matter of his paintings, I thought of how this imagery contributed to westward expansion and the colonization of America. And as an historian, of course I thought of Fredrick Jackson Turner in his influential essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” which was first presented in 1893. Turner’s thesis argued that the American frontier experience had played a fundamental role in shaping American identity, culture, and democracy. This wasn’t good news for those displaced and forcibly removed from their ancestral lands, let alone the deaths that occurred at the hands of these colonists, but these visualizations were powerful motivators and contributed to the American sense of exceptionalism.

Depiction of the Frontier as a Source of American Identity:

Turner’s thesis proposed that the existence of the American frontier had a profound impact on the development of American characteristics, including individualism, self-reliance, and a sense of democracy. Bierstadt’s paintings of the American West, with their vast, untamed landscapes and sense of limitless opportunity, visually reinforce Turner’s idea of the frontier as a defining aspect of American identity. Imagery like this pictured the West as an empty geography that promoted ideas such as Manifest Destiny, a perennial issue to us Canadians.

Bierstadt’s works often showcased the frontier as a land of grandeur and natural splendor. His paintings, such as “The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak,” conveyed the idea that the frontier was a place of both challenge and beauty, where Americans could test their mettle and forge a unique national identity. Light and luminance plays a key role in his work.

Romanticizing the Frontier:

Frederick Jackson Turner argued that the American frontier was not just a geographic place but also a state of mind, a crucible where American values and democracy were forged. Bierstadt’s art embraced the Romanticism movement, which sought to evoke deep emotional connections with nature. By depicting the frontier with awe-inspiring landscapes, he contributed to the romanticization of the West, portraying it as a land of boundless promise and adventure.

Encouraging Westward Expansion:

Turner believed that the closing of the frontier, symbolized by the U.S. Census Bureau’s declaration that the American West was no longer an unsettled frontier in 1890, marked the end of an era. Bierstadt’s paintings, created during a time of westward expansion and exploration, played a role in inspiring people to head west in search of opportunities, contributing to the westward movement that Turner highlighted in his thesis.

Bierstadt’s artworks conveyed the idea that the frontier was a place where dreams could be realized, encouraging settlement and exploration, which were central themes in Turner’s thesis. His paintings portrayed the West as a vast, uncharted territory ripe for discovery (and exploitation).

Symbolizing the Closing of the Frontier:

Ironically, as Turner’s thesis emphasized the closing of the American frontier, Bierstadt’s later works, such as “The Last of the Buffalo,” depicted the impact of westward expansion on the wilderness and native populations. These paintings highlighted the environmental and cultural changes that accompanied the closing of the frontier, aligning with Turner’s concerns about the consequences of westward expansion.

Here are a few images that were created when ideating in midJourney with the keywords of Albert Bierstadt and “seascape”!

Beowulf, from Folio

Wow! The illustrations in the new edition of Beowulf from Folio are fantastic! I have read a few translations of this epic but not one that flows this well, especially when read aloud.

Beowulf is an epic poem composed in Old English, that delves into a tapestry of timeless themes that resonate across cultures and eras. At its core, it explores the intricate interplay between heroism, fate, and the human condition. The heroic exploits of the main character, Beowulf, exemplify the archetype of the hero as a valiant warrior who confronts monstrous adversaries to protect his people. Amidst the relentless battles and grand feats, the poem contemplates the inevitability of fate, illustrating the concept of wyrd, or destiny, that shapes the lives of both mortals and supernatural beings alike.

Like other “valiant warrior” archetypes from Gilgamesh, Arjuna in the Mahabharata, to Siegfried in the Nibelungenlied, Beowulf protects his people and upholds the ideals of loyalty and duty.

Through the tension between heroic action and the transience of human existence, Beowulf meditates on the impermanence of glory and the lingering echoes of one’s deeds. Philosophically, the poem serves as a window into the cultural values of the Anglo-Saxons, revealing their emphasis on courage, loyalty, and communal bonds. It encapsulates a world where heroic actions are both celebrated and tempered by a sense of melancholy, offering profound insights into the perennial struggle of humanity to navigate the dual nature of its aspirations and limitations. As a crucial piece of early English literature, Beowulf holds historical significance by providing a glimpse into the oral tradition of storytelling, while its thematic depth invites ongoing contemplation of the complexities inherent in the human experience.

Beowulf’s historical significance is most pronounced within the context of its original audience, the Anglo-Saxons. In a time characterized by tribal conflicts and cultural upheaval, the poem served as a vehicle for transmitting cultural values, moral lessons, and ancestral narratives. It encapsulated the ethos of warrior societies, reflecting the importance of heroic deeds, loyalty to one’s lord, and the communal bonds that held disparate clans together. Moreover, Beowulf’s Christian elements, juxtaposed with pagan spiritual themes, provide insights into the complex religious landscape of the period, underscoring the process of cultural and religious synthesis that marked the era’s transition. This synthesis is reflected in the poem’s exploration of the tension between the heroic code and the Christian notions of humility and salvation. As such, Beowulf not only preserves the tales of a bygone era but also mirrors the cultural dynamics, tensions and transformations that defined its historical context.

The role of monsters and ghosts within Beowulf extends beyond mere antagonists, serving as symbolic embodiments of the unknown, the monstrous, and the existential fears that have haunted humanity throughout time. The monsters, such as Grendel and his mother, represent both external threats and internal struggles. Grendel embodies the darkness lurking at the fringes of civilization, while his mother embodies the fierce maternal instinct and the vengeful aspects of femininity.

These supernatural beings serve as reminders of the impermanence of life and the inevitability of death. The dragon that Beowulf battles in his final heroic act symbolizes both the culmination of his heroic journey (Joseph Campbell is my guide here) and the fragility of human achievements in the face of time’s passage.

The defeat of these monsters by Beowulf showcases the triumph of human courage and prowess over primal forces. Furthermore, the dragon in the later part of the poem emphasizes the inevitability of mortality and the paradox of the hero’s quest for eternal fame. The supernatural beings in Beowulf, with their connections to the uncanny and the macabre, reflect the blurred boundaries between the real and the mythical in a world where the mysteries of existence often remained uncharted. In this way, the monsters and ghosts in Beowulf not only heighten the epic’s dramatic tension but also provide a lens through which to explore the psychological and existential dimensions of the human experience, offering a contemplative bridge between the mortal and the supernatural realms.

… the other, miscreated thing,

in man’s form trod the ways of exile,

albeit he was greater than any other human thing.

Him in days of old the dwellers on earth named Grendel

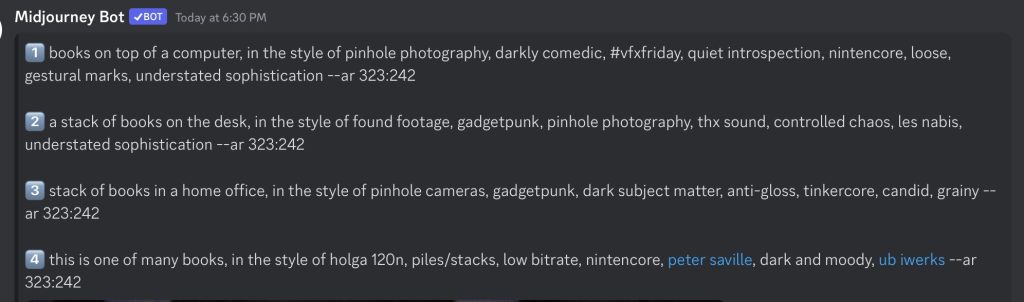

Mamiya RB67 + Digital Back + Midjourney

I finally received my digital back for my analog Mamiya RB67. I am having some focus issues but I have found leaving the shutter open helps with the testing. I will install the app and maybe that will help. But in the meanwhile I have been uploading my test shots to MidJourney for visualizations. Here are the prompts from the /describe command. I love some of the results although some of the prompts aren’t easily understood!

- books on top of a computer in the style of pinhole photography, darkly comedic, #vfxfriday, quiet introspection, ninetencore, loose gestural marks, understated sophistication –ar 323:242

- a stack of books on the desk, in the style of found footage, gadgetpunk, pinhole photography, thx sound, controlled chaos, les nabis, understated sophistication –ar 323:242

- this is one of many books, in the stule of holga 120n, piles/stacks, low bitrate, nintencore, peter saville, dark and moody, ub iwerks –ar 323:242

- stack of books in a home office, in the style of pinhole camera , gadgetpunk, dark subject matter, anti-gloss, tinkercore, candid, grainy –ar 323:242

I’m not sure what “nintencore” means but it appears twice. Holga and pinhole camera make sense though. I’m not sure how the algorithm “derived” this from the photo but here are the results!

And I used the new zoom out feature on the first MidJourney image above.

Adjusting Focus: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v-o6CN-0dAw

The Dynamic Nature of Mediated Experiences and the Evolution of Interpretation and Value Assigned to Hyperobjects

In today’s media-saturated world, where digital technologies and virtual spaces shape our perception and experiences, the concept of hyperobjects and their significance has gained increasing attention. Hyperobjects, as conceptualized by Timothy Morton, are entities that are massive in scale, extending beyond our immediate sensory perception and challenging our traditional modes of understanding. This essay explores the dynamic nature of mediated experiences and their profound impact on the interpretation and value assigned to hyperobjects over time. By examining the interplay between media, technology, culture, and the evolving historical context, we can gain insight into the complex and ever-changing relationship between humans and hyperobjects.

The interpretation and value assigned to hyperobjects have been subject to significant transformations throughout history, largely driven by advancements in media and technology. From the advent of print culture and the Enlightenment era to the rise of photography, cinema, and the digital age, each technological innovation has shaped the way we perceive and engage with hyperobjects. Media have played a crucial role in mediating our experiences, allowing us to comprehend and interpret hyperobjects in distinct ways across different historical periods.

The interpretive frameworks through which hyperobjects have been understood and valued have evolved alongside media and technological advancements. Early on, hyperobjects were often perceived through religious or metaphysical lenses, representing the sublime and the ineffable. However, with the rise of print culture and scientific discoveries, hyperobjects came to be interpreted through rational and empirical frameworks. The Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and empirical observation provided new ways of understanding and valuing hyperobjects based on their material properties and measurable characteristics.

The invention of photography in the 19th century introduced a significant shift in the interpretation and value assigned to hyperobjects. Walter Benjamin’s concept of the aura, intertwined with the reproducibility of art, offers valuable insights into this transformation. Through the lens of photography, hyperobjects could now be reproduced, detached from their original context, and disseminated widely. This democratization of access to hyperobjects challenged the traditional notions of uniqueness, authenticity, and aura, altering their interpretation and value in the eyes of viewers.

The emergence of cinema as a mass medium further transformed the interpretation and value assigned to hyperobjects. Marshall McLuhan’s media theory provides a lens to understand how cinema, as an extension of human senses, altered our temporal experience of hyperobjects. Through the cinematic medium, hyperobjects could be captured in motion, extending beyond the boundaries of time and space. This temporal dimension introduced new ways of perceiving and interpreting hyperobjects, emphasizing their dynamic and evolving nature.

The advent of digital technologies and the proliferation of the internet have brought forth a new era of mediated experiences with hyperobjects. The concept of hyperobjects has become intertwined with the digital realm, as the internet facilitates widespread access, participation, and engagement with these massive entities. The dynamic and interactive nature of digital media allows for multidimensional encounters with hyperobjects, enabling individuals to contribute to their interpretation, value, and even co-creation. Online platforms and social media provide spaces for collective discussions, collaborative engagement, and the formation of diverse interpretive communities around hyperobjects.

It is crucial to recognize that the interpretation and value assigned to hyperobjects are deeply intertwined with cultural contexts and socio-political dynamics. Different cultural perspectives and historical narratives shape the ways in which hyperobjects are understood, valued, and integrated into collective consciousness. The meaning and significance of hyperobjects can vary across cultures, reflecting the diverse ways in which societies interact with and perceive their surrounding environments.

Mediated experiences have significantly influenced the interpretation and value assigned to hyperobjects over time. From print culture to photography, cinema, and the digital age, each technological advancement has shaped our perception and engagement with these massive entities. The evolution of interpretive frameworks, the democratization of access through reproducibility, the temporal dimension of cinema, and the interactive nature of digital technologies have all contributed to the dynamic nature of our relationship with hyperobjects. Furthermore, cultural contexts play a crucial role in shaping the meaning and significance attributed to hyperobjects, emphasizing the diverse ways in which societies understand and value these entities.

Understanding the dynamic nature of mediated experiences and their impact on the interpretation and value assigned to hyperobjects provides valuable insights into our evolving relationship with the world and the ecological challenges we face. By critically examining the interplay between media, technology, culture, and historical context, we can better comprehend the complexities surrounding hyperobjects and develop more nuanced and informed approaches to engage with these vast and interconnected entities in the present and future.

Thinking with my LLM* v.1 – Benjamin, Sloterdijk, and Harman

*apologies to Gerhard Richter who I stole this from. His work Thinking with Adorno is quite close to a form of analysis that I practice. An un-coercive gaze that builds on, among others, Walter Benjamin, Bruno Latour and Graham Harman.

Drawing connections between Walter Benjamin’s notions of looking and seeing in “The Arcades Project” and Graham Harman’s aesthetics of art, while incorporating elements of Peter Sloterdijk’s concept of spheres, can yield an intriguing perspective on the relationship between perception, aesthetics, and the formation of social and cultural spheres.

In “The Arcades Project,” Benjamin explores the phenomenon of flânerie, the act of strolling and observing the cityscape, particularly the 19th-century Parisian arcades. Benjamin emphasizes the significance of attentive looking and seeing, as the flâneur engages with the urban environment and becomes attuned to the hidden meanings and historical layers embedded within it. This mode of perceptive engagement, for Benjamin, unveils the dialectical interplay between past and present, as well as the social and cultural forces shaping the urban experience.

On voit un chiffonnier qui vient, hochant la tête,

Butant, et se cognant aux murs comme un poète,

Et, sans prendre souci des mouchards, ses sujets,

Epanche tout son coeur en glorieux projets.*

*Charles Baudelaire: ‘Le Vin de Chiffonniers’ (‘The Ragpicker’s Wine’). As an aside, Philip Guston’s artwork post-Marlborough is deeply connected to Benjamin’s visual thinking, especially in the forms and stories of the suicide of his father, a “ragpicker”.

Benjamin, extending the Freudian imperative through the aesthetics of the gaze, implicates visualization as a form of “empathy with the exchange value itself”, absorbing an underlying dynamic tension between various notational modes of perspective, i.e. spherical and linear ontologies. Baudelaire’s flaneur demands a visual space later filled by, amongst other things, cubism.

Harman’s aesthetics of art, rooted in his object-oriented ontology, introduces a perspective where artworks possess their own withdrawn essence or allure. According to Harman, art objects, such as paintings or sculptures, have a hidden depth that eludes full comprehension or immediate access. Aesthetic encounters with art involve a form of sensual engagement where the viewer and the object enter into a unique relationship, unveiling new perspectives and opening up possibilities for understanding.

By linking Benjamin’s notion of attentive looking and seeing with Harman’s aesthetics of art, we can perceive a parallel in their emphasis on a nuanced engagement with the world, where the act of perception becomes a transformative encounter. Just as Benjamin’s flâneur scrutinizes the urban landscape, the viewer of art becomes an active participant in the aesthetic experience, probing the depths of the artwork and engaging in a dialogue that extends beyond the immediate perceptual realm.

In this context, Sloterdijk’s concept of spheres becomes relevant. Spheres, as conceptualized by Sloterdijk, represent enclosed spaces that shape human existence and foster particular social and cultural dynamics. Artistic encounters, influenced by Benjamin’s attentive looking and Harman’s aesthetics, can be seen as moments of sphere formation. The viewer, the artwork, and the surrounding context coalesce to create a temporary sphere, an experiential space where new meanings emerge, and shared interpretations are forged.

This Sloterdijkian sphere of artistic encounter allows for a collective engagement with art, where individuals come together within a shared sphere of perception and interpretation. It is within these aesthetic spheres that cultural and social values, ideas, and identities are negotiated, challenged, and constructed.

By linking Benjamin’s notions of looking and seeing, Harman’s aesthetics of art, and Sloterdijk’s concept of spheres, we can explore the interplay between perception, aesthetic experience, and the formation of social and cultural spheres. These connections highlight the transformative potential of art and the profound impact it can have on the formation of collective meaning and understanding.

Walter Benjamin and Digital Storytelling

Tl/Dr

This text explores the intersection of data ethics and data literacy and the role of data storytelling in the digital era. The author draws an analogy between photography and data, highlighting their potential to challenge dominant cultural narratives or perpetuate oppressive systems of power. The importance of critical thinking and data literacy skills to approach both photography and data storytelling with a critical eye is emphasized, along with the significance of ethics in data storytelling. The author argues that ethical considerations are essential in data storytelling, as data can be misused, misrepresented, or distorted. Finally, the importance of data quality and integrity is highlighted, and the consequences of unethical data storytelling are discussed.

The Art of Data Storytelling: The Intersection of Data Ethics and Data Literacy

I just finished reading a book on visual culture by Walter Benjamin, a European philosopher and cultural critic from the early 20th century. His work from almost a century ago was about photography and its place as a tool for storytelling in the “modern world”. I felt compelled to blog about how data plays that same role in the digital era. Notes that I had taken from Benjamin’s published and secondary works seem particularly relevant and they guide my account below. For Benjamin, photography was both a tool and the content for modernity, much how data has assumed that role today. Many of the same important ethical considerations that was raised by Benjamin are relevant today.

Walter Benjamin, photography and modernity

Benjamin’s use of photography to illustrate his ethical position was complex. He recognized both the potential of photography to challenge dominant cultural narratives and to give voice to the marginalized, as well as its ability to perpetuate oppressive systems of power. By using photography in his writing, Benjamin was able to articulate a nuanced ethical position that emphasized the importance of resisting oppressive social structures while challenging dominant cultural narratives.

One analogy between data and photography is that data can be thought of as the “raw material” of information, in the same way that photographs can be seen as the “raw material” of visual representation. Just as a photographer captures an image and then develops and manipulates it to create a final product, data can be collected, processed, and analyzed to create meaningful information.

Similarly, just as a photograph can capture a specific moment in time and convey a particular perspective or interpretation of reality, data can provide a snapshot of a particular phenomenon or aspect of the world. Both photography and data can be used to document and communicate information, and both can be subject to manipulation and interpretation depending on the perspective of the person creating or analyzing them.

Additionally, like photography, data can be used for both positive and negative purposes. Photography can be used to capture beautiful images, convey powerful messages, and expose social injustices; however, it can also be used to perpetuate harmful stereotypes or to invade people’s privacy. Similarly, data can be used to drive innovation, inform decision-making, and advance scientific understanding. However, it can also be used to perpetuate discrimination, violate individual rights, and reinforce power imbalances.

Benjamin, writing over a century ago, believed that storytelling was a powerful tool for communicating and interpreting the world around us. He argued that storytelling was a way of making sense of the world, and that it had the ability to reveal hidden truths and challenge dominant narratives. From Benjamin’s perspective, what we call data storytelling could be seen as a way of revealing the hidden truths within complex datasets and challenging dominant narratives. In our case, narratives about immigration, settlement, and integration.

Anna Rosling Ronnlund has an amazing TED Talk on this titled See How the Rest of the World Lives, Organized by Income, showing photographs of where people live. There is a geography and a history – a time and a space – to inequality that, when seen, conveys additional contextual data that tables and charts and numbers cannot capture. The standardization of data is maintained through “common object” photography. The same items are photographed for all interactions, bed or the children’s toys, for example.

Photography, data and storytelling ethics

An analogy between photography and data storytelling is that both are powerful tools for communication and can be used to convey complex information in a compelling and accessible way. Just as a photograph can tell a story and capture the essence of a moment or a scene, data storytelling can use visualizations, narratives, and other techniques to communicate the insights and meaning behind data.

In photography, the composition, lighting, and framing of an image can all contribute to the message and emotion conveyed. Similarly, in data storytelling, the way that data is visualized, organized, and presented can all influence how the story is perceived and understood.

Both photography and data storytelling can have a significant impact on the audience. A powerful photograph can evoke strong emotions and spark action, while a compelling data story can inform decision-making and inspire change. Both photography and data storytelling can also reveal important insights and perspectives that might otherwise go unnoticed.

However, it’s also important to note that both photography and data storytelling can be subject to manipulation and interpretation, that’s why critical thinking and other data literacy skills are important. Just as a photograph can be edited or cropped to change its message or impact, data can be selectively chosen or presented to support a particular narrative or agenda. Therefore, it’s crucial to approach both photography and data storytelling with a critical eye and a willingness to question assumptions and biases recognizing that data storytelling also raises important ethical considerations, particularly when it comes to the privacy and security of the individuals represented in the data.

The significance of ethics in data storytelling is paramount. Without ethical considerations, data can be misused, misrepresented, or distorted. Data storytelling can shape public opinion and inform government policy. However, in some cases, data can be manipulated to serve political or other personal interests.

Data Quality and Integrity

The integrity of the data used in data storytelling is essential to ensure ethical decision-making. It is vital to ensure that the data used is accurate and reliable, free from any manipulation, errors, or biases. Data should be collected, stored, and analyzed in a transparent and accountable manner to maintain its quality. Its governance has never been so important.

The Impact of Unethical Data Storytelling

The consequences of unethical data storytelling can be severe. Misleading data can lead to policy decisions that are not in the best interest of the public, or worse, policies that harm specific groups. In the context of immigration policy, using data that is biased or unreliable can result in discriminatory policies or decisions. For instance, if data is manipulated to support a narrative that certain groups are less deserving of Canadian citizenship or permanent residency, this could result in policy decisions that are unfair and unjust

Data Storytelling as a Tool for Engagement

Data is a valuable resource for policymakers, but simply presenting data is not enough to effectively engage with the public. To make data meaningful and relevant, policymakers need to transform data into stories that are relatable and engaging. This is where data storytelling comes in, a practice that combines the analytical rigour of data analysis with the creativity of art. By presenting data in a narrative format, data storytelling can help create an emotional connection with the audience and make the data more accessible. However, it’s important to note that data storytelling isn’t just about making data more interesting, but also making it more informative and accurate. By combining the power of storytelling with data analysis, data storytellers can make policy issues accessible and engaging to a wider audience.

The Art of Data Visualization

Data visualization is a critical component of data storytelling, and it is often said that a picture is worth a thousand words. Data visualizations allow policymakers to convey complex information in a way that is intuitive and easily understandable. However, not all data visualizations are created equal. Effective data visualizations must be visually appealing, easy to read, and accurately represent the data. In the context of immigration, settlement, and integration data, effective visualizations can help policymakers communicate the impact of policy decisions on real people’s lives.

As Walter Benjamin wrote, storytelling is a never-ending source of information about ourselves and the world. Data visualization can be seen as a form of storytelling that can communicate complex data in a simple and engaging way. By weaving a narrative into data visualization, we can create an emotional connection with the audience and provide them with a memorable experience.

One example of the power of storytelling in data visualization is the data-driven storytelling project by the New York Times called “The Upshot”. This project combines data visualization with storytelling to create a powerful tool for understanding complex issues such as climate change and political polarization.

Another example are the data visualization projects by the Human Rights Data Analysis Group. One of the especially compelling ones is called “Say Their Names”, that uses data visualization to tell the stories of victims of police brutality in the United States. By combining data with storytelling, this project has created a powerful tool for raising awareness and advocating for change. Check that out here: https://hrdag.org

Data visualization is a critical tool for understanding complex data and communicating insights to decision-makers. By following best practices and incorporating storytelling, we can create powerful visualizations that empower people to make data-driven decisions. However, it is essential to be aware of the challenges in data visualization and take steps to address them to ensure that the visualization is reliable and effective. And not just this, but it is important to embrace the art of data visualization as a means to preserve and communicate knowledge to future generations. Benjamin again, “Every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.”

This is our story. These are our stories.

Our Responsibility

Policy researchers and data scientists have a moral obligation to ensure ethical data storytelling. The collection, analysis, and interpretation of data should be done with the utmost care, transparency, and accountability. This includes using reliable sources of data, ensuring that the data is analyzed in a manner that is free from bias, and presenting the data in a manner that is accessible and understandable to policymakers and the public.

Moreover, policy researchers and data scientists should engage with stakeholders and communities to ensure that the data is representative of the population it seeks to describe. This includes consulting with community leaders, advocates, and organizations to ensure that the data reflects the lived experiences of those affected by government policies.

The ethical considerations of data storytelling in government policy-making are of utmost importance. Policy researchers, analysts, and data scientists have a moral obligation to ensure that the data used is of high quality, transparent, and accountable. The impact of unethical data storytelling can be severe, resulting in policy decisions that are discriminatory, unfair, and unjust. It is important to ensure that the stories we tell are based on accurate data and do not reinforce harmful stereotypes or biases. Our responsibility is to ensure that data storytelling is done ethically, transparently, and accountably to uphold the public’s trust and confidence. There is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism. We must be careful to use data storytelling to advance positive change rather than perpetuate harmful narratives.

More places that don’t exist!

I am now much more efficient at wasting my time in midJourney. ChatGPT to the rescue. I am using a modified prompt generator that, in this case, is photography specific. The outline was from the message board and I forgot to note the user but much respect. I will make another post with my prompt generator that blends artists together.

Act like an Pulitzer Award winning documentary film photographer using poetic and beautiful composition techniques. Please write without wordwraps and headlines, without connection words, back to back seperated with commas:

[1], [2], [3] {daylight}, [4], [5] {Hassleblad}

replace [1] with the subject: "building schematic"

replace [2] with a list of detailed descriptions about [1]

replace [3] with a list of detailed descriptions about the environment of the scene

replace [4] with a list of detailed descriptions about the mood/feelings and atmosphere of the scene

replace [5] with a list of detailed descriptions about the camera brand / cameral model / lens / aperture / film type and sensor resolution details

Your output should be a complex prompt for an AI-based text to image program that converts a prompt about a topic into an image. The outcome depends on the prompts coherency. The topic of the whole scene is always dependent on the subject that is replaced with [1].

always end the prompt with "--ar 16:9"

don't use any line breaks

Very important, limit yourself to 80 words.