On my current reading list: Postsensual Aesthetics: On the Logic of the Curatorial on the dialogue on the aesthetic dimensions of the exhibition form.

Philip Guston’s 1970 Marlborough exhibition included many paintings on show in London at the Tate Modern in 2023-24. The 1970 show offers a compelling case study in the interplay between sensory engagement, cognitive exploration, and spiritual introspection in contemporary art. As the art world continues to grapple with shifting paradigms—where conceptual rigour often eclipses immediate sensory experiences—Guston’s late works provide a critical counterpoint. His return to form underscores a nuanced dialogue between these dimensions, inviting viewers to reevaluate the intersections of sensuality, intellect, and mysticism in art.

In this context, Guston’s work serves as a crucial reference point for understanding the evolution of art exhibitions and their role in shaping contemporary aesthetic discourse. The Marlborough exhibition’s reintroduction of sensuality into the artistic conversation aligns with Voorhies’ vision of a post-sensual aesthetic, where the interaction between sensory immediacy and cognitive engagement defines the art of today.

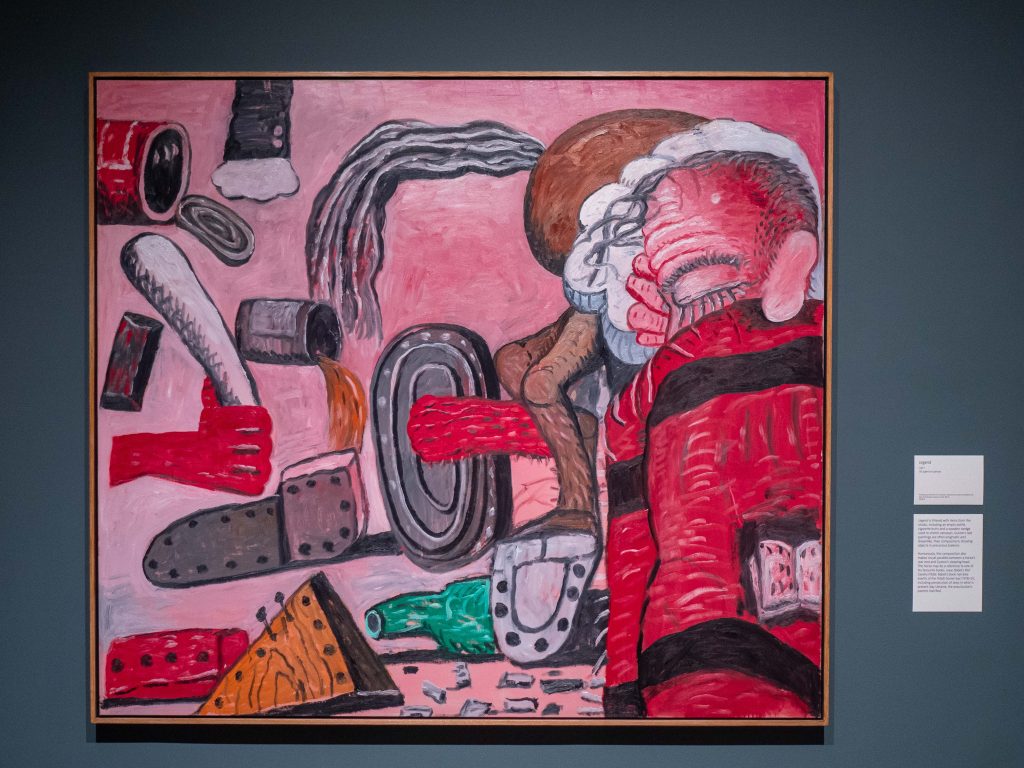

In Guston’s Marlborough presentation, the artist’s signature late style—characterized by its raw, almost crude materiality—emerges as a profound statement on the sensual dimensions of art. Guston’s use of thick impasto, gritty textures, and a palette imbued with vibrant, often unsettling colours reinvigorates the sensual experience of painting. Not to mention the subject matter including his family and personal insights. This return to a more tactile, visceral approach contrasts sharply with the clean, cerebral aesthetics that dominated much of the mid-20th century art scene. It certainly was a large departure from his abstract expressionist pedigree.

The tactile quality of Guston’s work in this exhibition was not merely about surface texture but about creating an embodied sensual, perhaps visceral, experience. The rough brushstrokes and heavy application of paint confront the viewer, demanding a physical and emotional engagement that resists easy interpretation. Like Auerbach, his works are architectonic. This materiality recalls the sensory immediacy of earlier artistic traditions while simultaneously addressing the complexities of modern experience.

Guston’s later works do engage with cognitive and conceptual concerns, though not in the abstract sense of his earlier work. Instead, these paintings offer a complex commentary on the personal and political dimensions of art. The Marlborough exhibition highlighted this cognitive dimension through Guston’s use of recurring motifs—such as hooded figures, allusions to early Tuscan art and ambiguous symbols—which invite viewers into the personal and socio-political narratives embedded within the works. This interplay between recognizable forms and abstracted meanings challenges viewers to engage in a process of negotiating between the immediacy of the sensory experience and the layers of cognitive interpretation.

Guston’s intellectual engagement also reflects his admiration for the Tuscan Renaissance, particularly the work of Piero della Francesca. This influence is evident in the geometric precision and compositional clarity found in his late works, not to mention deeper connections to the works for his patron, Federico da Montefeltro. Guston’s fascination with Piero’s use of space and perspective reveals a deep appreciation for the intellectual rigour and formal discipline of Renaissance art. The clarity and structure of Piero’s compositions echo in Guston’s own work, where the abstraction of form serves to underscore deeper conceptual themes.

Guston’s admiration for Renaissance masters like Piero della Francesca is also indicative of his spiritual and contemplative inclinations. The spiritual, serene, almost mystical quality of Piero’s work, with its emphasis on clarity and transcendence, mirrors Guston’s own quest for deeper meaning and introspection. The contemplative nature of Piero’s compositions—often imbued with a sense of timelessness and stillness—parallels the reflective quality found in Guston’s late paintings.

Philip Guston’s Marlborough exhibition exemplified a compelling synthesis of the sensory, cognitive, and spiritual dimensions of art. By returning to a more visceral and material approach while also reengaging with complex personal and political themes, Guston creates an experience that transcends simplistic categorizations. His late works challenged the dominant trends of conceptual abstraction and intellectualization, offering a richer, more nuanced engagement with art.

Guston’s return to figuration and raw, emotive styles in the Marlborough exhibition represented a dramatic departure from the intellectual rigors of Abstract Expressionism. Where his earlier work was characterized by abstract complexity and a focus on psychological and emotional depth, this exhibition reintroduced a visceral, tactile engagement with the viewer. The shift was not merely a stylistic change but a recalibration of art’s role in eliciting an immediate, sensory response—a move away from the cerebral and toward a more embodied, sensory experience.

This exhibition also underscored Guston’s deep intellectual engagement with historical art traditions, particularly his admiration for Renaissance masters like Piero della Francesca. His incorporation of these influences added a layer of cognitive depth to his work, enriching the dialogue between sensory immediacy and intellectual exploration.

Guston’s work invites us to explore the interplay between sensory experience, intellectual engagement, and spiritual reflection, reaffirming the capacity of art to engage with the full spectrum of human experience. In an era where the cognitive often overshadows the sensory, and where spiritual concerns are frequently sidelined, Guston’s return to form provided a vital and invigorating counterpoint that may be insightful when considering contemporary discussions of exhibitions.

In this light, Guston’s Marlborough exhibition can be seen as an early, intuitive exploration of Voorhies’ postsensual aesthetics. The exhibition’s emphasis on sensual engagement through expressive, figurative works aligns with Voorhies’ call for a renewed appreciation of sensory experience, even as it acknowledges the importance of cognitive and intellectual dimensions. Guston’s work reaffirms the necessity of engaging both the senses and the intellect, illustrating how art can bridge the gap between immediate sensory impact and deeper conceptual reflection.

Voorhies’ theoretical framework reframes aesthetic criteria to encompass both the immediate and cognitive dimensions of art, recognizing the significance of both sensual and intellectual engagements. Guston’s Marlborough show, with its return to a more visceral and immediate form of art, exemplifies this duality, highlighting the ongoing relevance of sensory experience within a broader, cognitively enriched aesthetic landscape.