“After a lifetime, I still have never been able to escape my family…. It is still a struggle to be hidden and feel strange—my favorite mood.” Philip Guston

In the latter part of Philip Goldstein’s career (he changed his name to Guston evidently due to his fear that his Jewish last name would affect his relationship with his future wife Musa’s Catholic parents), his work underwent a dramatic transformation, marked by a shift from abstract to figurative painting. This transition, initially met with skepticism and insult, reveals a profound engagement with asemic expression—a mode of art that communicates beyond the constraints of language. Guston’s late paintings, exemplified in the Marlborough Gallery show in 1970, provide a compelling example of how asemic art can serve as an intensely personal and symbolic language.

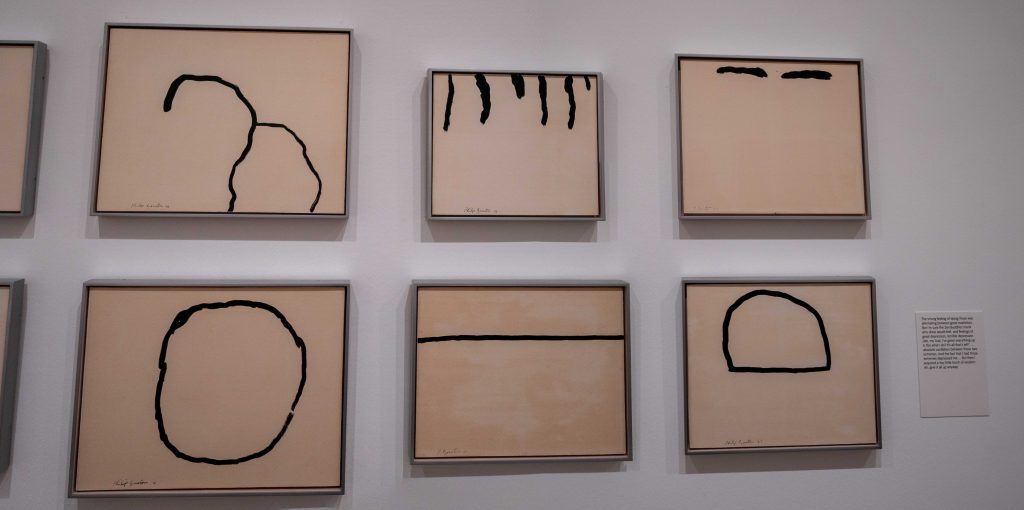

Asemic art describe works that function as a form of visual writing without specific semantic content, plays a crucial role in Guston’s late career. His paintings from this period do not follow a clear narrative or linguistic structure but instead use cartoon-like forms and symbols to evoke emotional and intellectual responses. This approach allows Guston to engage with complex personal and universal themes in a way that transcends conventional language.

Guston’s late canvases are rich with personal symbolism and emotional depth, reflecting his life experiences and inner turmoil. They are portraits of his life. Archie Rand once wrote that: Philip adopted Italian culture … actually thought of himself as someone in the tradition of those people who learned the visual language that meant to be Italian, and basically, what it meant to be Catholic. Certain rules of veneration, which Judaism not only doesn’t share, but rejects. The notion of authoritative leadership was rejected by someone who was reclaiming his identity. Guston had this conundrum: he had to transfer that reverence to himself and his experience.

This period of his work can be viewed through the lens of asemic expression, where the visual elements of the paintings operate like a silent text, conveying complex layers of meaning without relying on explicit narrative or linguistic content. His use of crude, cartoonish figures and mundane objects becomes a form of asemic writing, evoking personal and universal themes in a manner that transcends verbal description.

The influence of historical artists, particularly Piero della Francesca and his iconic portraits, provides a valuable context for understanding Guston’s late work. Piero’s portraits of Federico da Montefeltro and his wife are renowned for their meticulous detail and compositional precision. In these portraits, the chariots on the obverse of the canvas—can be seen as symbolic elements that resonate with Guston’s late work. Guston’s cars, depicted with a similar sense of mechanical and symbolic weight, echo the chariots of Piero’s portraits. This connection underscores a thematic continuity between Guston’s personal symbols and historical references.

Philip Guston held a deep admiration for the work of Piero della Francesca, whose innovative approach to form, perspective, and symbolism resonated with Guston’s own artistic pursuits. Francesca’s mastery of these elements not only influenced Guston’s early development but also eased the stylistic changes in the late stages of his career. As Guston began to reintegrate recognizable forms into his paintings, he drew upon the techniques and innovations of Francesca, whose work provided a foundational understanding that supported Guston’s exploration of narrative and symbolic content in his late, figurative works.

It is true that Guston’s early life in California was menaced by organizational violence and racism. Guston’s 1930s art initially shocked audiences with its unflinching critique of its subjects. Conspirators, for instance, was created in the same bold style as a piece commissioned by the John Reed Club, a Communist Party-affiliated group, which had asked Guston to address the plight of the “American Negro.” This work centers on the Scottsboro Boys—nine Black teenagers wrongfully accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931. In one of Guston’s panels, a Klansman is depicted whipping a nearly nude figure bound to a stake resembling the Washington Monument.

However, the hoods in Guston’s late paintings take on a deeper, asemic significance when viewed through the lens of Piero’s portraits of his patron, the Duke of Montefeltro. The hoods’ shape and form can be seen as mimicking the noses of Federico da Montefeltro and his wife, creating a subtle yet profound dialogue between Guston’s personal imagery and historical iconography. This resemblance suggests that the hoods may function not just as symbols of societal and racial violence but also as personal emblems, representing Guston and his wife, Musa. In this interpretation, the hoods become a form of asemic portraiture, an intimate representation of the artist’s relationship and personal life.

Guston’s late paintings can be seen as asemic love poems to his wife and daughter, both named Musa. Much like Piero della Francesca’s reversible diptych of the Duke and his wife, which creates a dual narrative through its composition, Guston’s work offers a visual language that invites multiple interpretations. The cars, feet, and hooded figures contribute to a deeply personal, emotional narrative that defies straightforward explanation. Instead, they encourage viewers to engage intuitively and emotionally, drawing connections based on their own experiences and perceptions. On one level, Guston’s work reflects a commentary on societal and racial violence, echoing themes from his earlier work. On another, it functions as personal symbology, representing Guston’s own experiences and relationships. Through asemic phenomenology, Guston creates a visual ontology that transcends conventional representation, exploring themes of identity, memory, and personal trauma in a way that is aesthetically and profoundly intimate.

By employing asemic forms, Guston crafts a dialogue between the viewer and the canvas that is open to personal interpretation – freedom from the constraints of explicit meaning. This approach invites the audience to confront their own memories and emotions, forging a connection that is deeply personal and subjective. Guston’s asemic writing and imagery encourages an exploration of the self, where viewers can project their own experiences and feelings onto the artwork. In doing so, Guston not only reflects his own inner world but also provides a space for others to engage in their own introspective journeys, making the artwork a shared yet uniquely individual experience.

Philip Guston’s 1970 painting Flatlands can also be intriguingly compared to Roman decorative art forms, despite its modern reinterpretation. The painting features a flat, expansive surface populated with distorted figures, cartoon forms, and mundane objects, which serve as focal points similar to the “tabulae” or plaques in Roman villas. These elements, though not literal medallions, act as central motifs that draw the viewer’s attention and contribute to the composition’s rhythm. Guston’s use of circular forms and motifs in Flatlands evokes the essence of “medallions,” while the placement of figures and objects within the canvas creates a spatial organization reminiscent of “niches” found in Roman decoration. The tactile quality of Guston’s brushstrokes and layering adds a sculptural dimension to the painting, paralleling the “reliefs” of Roman art. In this way, Flatlands engages with classical principles of decoration by incorporating central motifs, spatial depth, and a textured approach, inviting viewers to explore its rich visual and symbolic layers.

Philip Guston first went to Rome in 1948 after winning the Prix de Rome, an award that allowed him to study and work in Italy. During this initial visit, Guston immersed himself in the study of Italian Renaissance art, particularly the works of Piero della Francesca, which profoundly influenced his sense of form and composition. He returned to Rome multiple times throughout his life, including significant stays in the late 1960s and early 1970s, including right after the opening of the Marlborough show. These later visits came during a period of intense personal and artistic transition, as he moved away from abstraction toward a more figurative style. Italy’s rich artistic heritage, combined with its historical and cultural layers, became a wellspring of inspiration, shaping the symbolic and narrative elements that would define his late work. This includes not only visual arts but also puppetry, poetry and theatre.

In this light, Guston’s late work emerges as a deeply personal and symbolic exploration of love, loss, and memory. His asemic approach to art allows him to communicate complex emotional truths without relying on conventional forms of representation. The paintings become a form of visual poetry, capturing the essence of his personal experiences and relationships in a way that is both evocative and elusive. In this context, the act of painting itself becomes a ritual of sorts, where each stroke of the brush is imbued with a sense of the sacred. The abstract forms and symbols in Guston’s work function similarly to the Kabbalistic symbols, aiming to reveal hidden truths and connect with the divine. His paintings thus operate as a form of visual mysticism, inviting viewers to engage with the work on a deeper, more intuitive level.

His paintbrush assumes the role of an asemic wand, channeling an almost magical quality into his compositions. This transformation reflects Guston’s life long engagement with mystical Judaism, as the brush becomes a tool for unveiling hidden meanings and invoking the ineffable. “Our whole lives (since I can remember) are made up of the most extreme cruelties of holocausts. We are the witnesses of the hell,” he wrote his friend, the poet Bill Berkson. Much like a magician’s wand conjures unseen forces, Guston’s brushwork channels a visual language that transcends verbal articulation, embodying the esoteric and the mysterious. His paintings, infused with symbols and sometimes recognizable forms, resonate with the rich traditions of Kabbalistic thought, where the act of creation itself becomes a form of mystical revelation, a revelation of what Walter Benjamin calls an aura. Through an asemic approach, Guston’s art transcends conventional symbolism, engaging with a deeper, spiritual dimension that speaks to the unseen and the sacred.

In Guston’s late work, shadows are not merely decorative elements but integral components that sculpt the space within the canvas. Unlike traditional applications where shadows serve to replicate natural lighting or add realism, Guston’s shadows assume an almost sculptural presence. They create a dynamic interplay between light and dark, visible and hidden, that enhances the emotional and symbolic content of his paintings.

In this reimagined use of shadows, Guston moves beyond mere chiaroscuro to engage with shadows as a form of emotional and psychological articulation. The heavy, often exaggerated shadows do not simply create depth but rather become an active force in the composition, reflecting the Kabbalistic concept of Sitra Achra—the “Other Side” or realm of darkness and concealment that contrasts with divine light. In Kabbalah, darkness represents hidden knowledge and existential challenge, themes that resonate deeply in Guston’s work. The shadows often envelop or distort figures and objects, emphasizing the tension between visibility and obscurity, clarity and ambiguity. This technique deepens the viewer’s engagement with the painting, as the shadows themselves become a language of their own, articulating the unsaid and the unseeable aspects of Guston’s personal and artistic journey.

Piero della Francesca’s was exposed to Eastern Orthodox concepts of divine light and darkness during the Council of Florence and they could have profoundly impacted his artistic approach. His precise use of mathematical perspective and light not only demonstrates his commitment to geometric principles but also can be seen to align with Orthodox theology’s mystical qualities, where divine light symbolizes spiritual illumination and shadows represent the struggle against spiritual darkness. Similarly, Philip Guston’s late work integrates Kabbalistic ideas, where shadows and asemic forms become vehicles for exploring personal trauma and existential reflection. Just as Piero’s mathematical rigour and theological depth blend to create a nuanced visual language, Guston’s incorporation of Kabbalistic darkness and abstract symbols enriches his work with a profound exploration of identity and emotion.

Guston’s approach to shadows often involves bold, contrasting areas of darkness that define and isolate forms. This technique not only contributes to the visual impact of his work but also plays a crucial role in shaping the viewer’s perception of the narrative and symbolic layers. The shadows in Guston’s paintings can be seen as an extension of his abstract language, providing a visual rhythm that resonates with the thematic concerns of his late work, such as personal trauma and existential reflection.

To fully appreciate the significance of Guston’s use of shadows, it is crucial to understand the techniques employed by Piero della Francesca, a master of Renaissance art renowned for his meticulous manipulation of light and shadow. Piero della Francesca identified primarily as a painter and mathematician. His writings, including De Prospectiva Pingendi (On Perspective in Painting), reflect his commitment to the study of geometry and perspective, which he integrated into his art. Piero’s paintings exemplify his sophisticated approach to creating depth and dimensionality through subtle gradations of tone. Although the term ‘chiaroscuro’—derived from the Italian words ‘chiaro’ (light) and ‘scuro’ (dark)—was not used in his time, his work illustrates the technique’s essence by using strong contrasts to enhance volume and spatial perception. In the Renaissance, shadows were essential for constructing perspective and form, similar to how a golem is animated into being.

In Jewish folklore, a golem is an anthropomorphic creature made from inanimate matter, often clay or mud, brought to life through mystical or divine means – a creative act. The golem is typically animated by inscribing sacred words or symbols on its body or placing a written charm, such as the Hebrew word “emet” (truth), on its forehead. By removing or altering this inscription (a form of erasure), the golem can be deactivated or rendered lifeless. This process of animating a golem symbolizes the transformation of the inanimate into the animate through the power of words or divine intervention. Similarly, in Renaissance art, shadows were used to transform flat, two-dimensional surfaces into lifelike, three-dimensional forms. Shadows added depth and perspective to paintings, giving them a sense of realism and volume, almost as if the painter had breathed life – an aura, into the static image through the manipulation of light and dark, colour and composition.

In Piero della Francesca’s work, shadows are meticulously crafted to enhance realism and serve a compositional role, defining the contours of figures and guiding the viewer’s eye to contribute to the harmony of the composition. This technique reflects the physical properties of light while adding symbolic depth, emphasizing the spiritual and psychological aspects of the subjects. Albrecht Dürer, in contrast, employed shadows with scientific precision to achieve intricate detail and texture, as seen in works like Melencolia I (a favourite of Guston’s). His shadows enhance depth and volume but focus more on detailed observation and intellectual engagement with the subject matter.

Guston’s shadows often assume an abstract quality, shaping forms to underscore their symbolic and emotional resonance rather than adhering to physical realism. For example, in Guston’s The Studio, shadows play a crucial role in transforming ordinary objects and figures into symbols that convey deeper psychological and existential themes. The interplay of light and shadow in The Studio creates an environment where the figures and objects are imbued with a sense of ambiguity and introspection. The shadows do not merely outline or define forms but rather contribute to a layered semiotic landscape that invites viewers to decode the personal and symbolic meanings embedded in the painting. This use of shadows diverges from Piero della Francesca’s more precise and measured chiaroscuro, which aims to achieve realistic volume and spatial depth. Instead, Guston’s approach reflects a modernist exploration of how shadows can serve as carriers of meaning, enhancing the emotional and symbolic complexity of his work.

Guston’s integrates non-semantic text-like forms into a deeply personal and introspective artistic practice. Guston’s use of asemic writing is not merely a visual experiment but a fundamental aspect of his phenomenological process, where the artist himself is the first and most critical audience. This approach reflects a profound engagement with his own emotional and existential experiences, as the asemic forms on the canvas become a medium through which he navigates and articulates his personal trauma. The abstract marks and fragmented text are not intended to convey explicit meaning but to resonate with Guston’s own sense of artistic satisfaction and knowledge formation. In this way, his work invites viewers to experience the artwork on a phenomenological level, reflecting the artist’s own process of exploring and understanding his inner world. Guston’s late paintings become a space where his self-reflective engagement with asemic writing transforms into a rich, sensory experience that is both introspective and emotionally resonant.

Philip Guston’s late paintings, as objects of profound knowledge formation, possess an aura akin to the golem. This aura, shaped by asemic phenomenology, conveys Guston’s emotional and existential state through abstract forms and asemic writing. Just as the golem is thought to embody hidden aspects of the creator and serve as vessels of personal and mystical insight, Guston’s works act as conduits for his inner reality. The sensory and emotional intensity of these paintings allows viewers to access Guston’s personal experiences and sense of self, transforming the artworks into a shared experience, a shared topography, where his intimate knowledge becomes vividly accessible.