Adam Tooze’s 2025 London Review of Books Autumn Lecture offers a diagnosis of a world whose organizing principles can no longer be captured by moral narratives or inherited geopolitical categories. The lecture is not concerned with adjudicating virtue or blame, but with understanding how power is materially organized, reproduced, and defended under contemporary conditions. What emerges is a picture of a global order under strain, not for lack of agency, but because it is saturated with it.

At the centre of Tooze’s argument is a shift in form rather than in substance. The age of hydrocarbons is not ending so much as being structurally transformed. The decisive change is not from oil to electricity alone, but from commodity based power to system based power. Oil could be owned, traded, and stockpiled; electricity must be generated, transmitted, and stabilized across networks. It is an architecture rather than an object. As a result, power is no longer primarily a matter of possession, but of coordination and governance, of shaping the conditions under which the system reproduces itself.

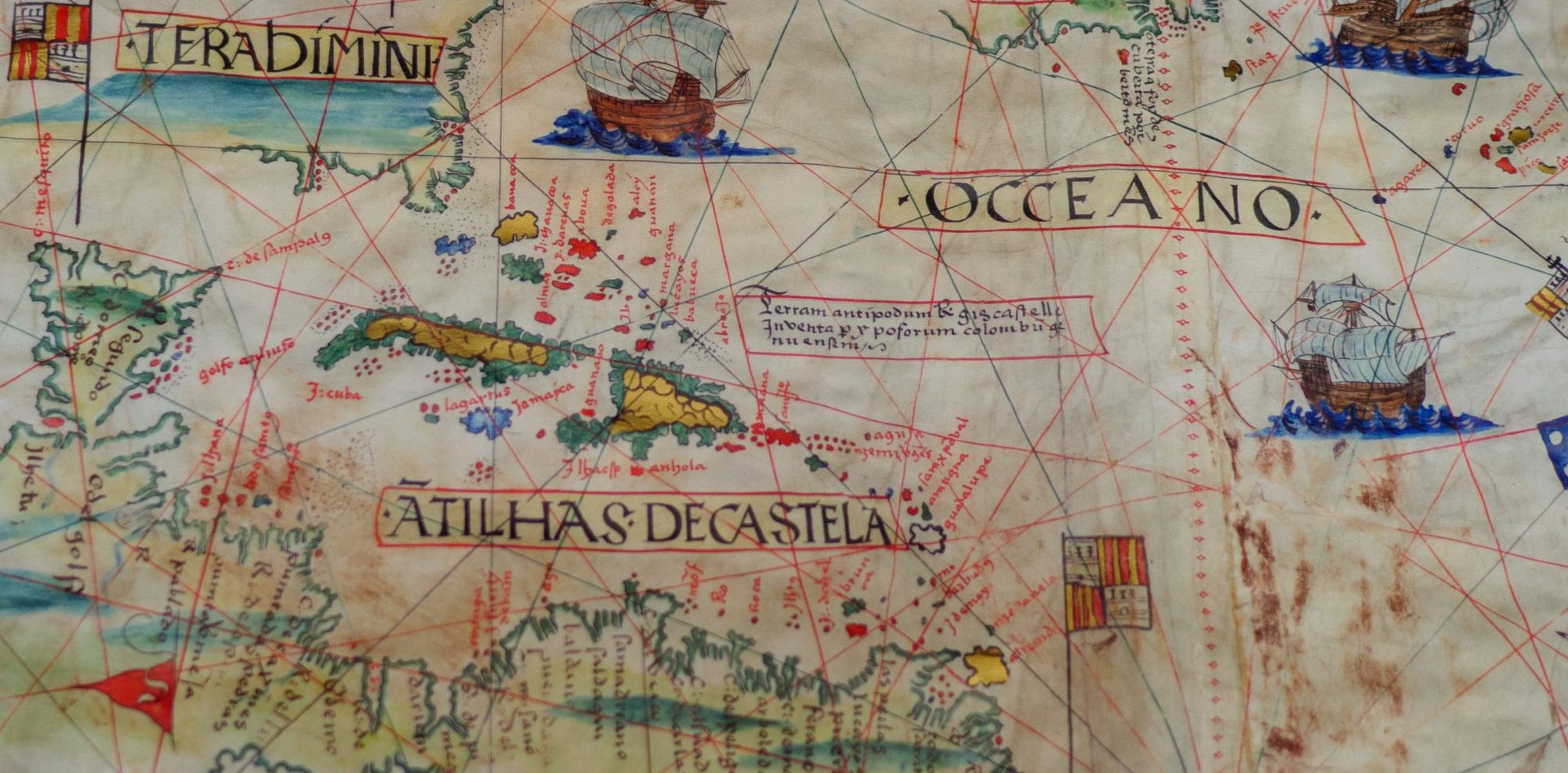

Tooze asks whether the present moment should be understood as a new Cold War. He rejects the simplistic claim that the world is returning to bipolarity, yet he emphasises that the logic of alignment is reappearing. If this framing is accepted, the analytic tools of the earlier struggle remain valuable: the core question is not ideological victory but the maintenance of asymmetric advantage. In this context, the logic of structural preponderance, pace Leffler, is transformed, shifting from industrial mobilization to infrastructural centrality. Twentieth century dominance rested on industrial capacity, military deterrence, and institutional reach; preponderance was a question of who could mobilize the greatest resources and sustain the largest war machine. Today, advantage is produced through infrastructural centrality. The state or coalition capable of designing, securing, and scaling energy systems, supply chains, and technological platforms can shape the strategic choices of others. Power resides less in what one controls directly than in the constraints and possibilities one imposes on the system as a whole. The imperative is not simply to be strong, but to ensure that rivals cannot develop comparable capacity on their own terms, and that their strategic options remain dependent on the architecture one controls.

It is against this transformed logic of preponderance that Tooze identifies one of the lecture’s most disquieting political dynamics. In order to preserve its strategic position, the United States aligns functionally with Russia and the Gulf states. This also works towards explaining recent American imperialism toward Venezuela. The alignment is not driven by shared ideology but by shared dependence on the stability of energy, finance, and infrastructure. Tooze resists the claim that the world has returned to a Cold War. The resemblance lies not in bipolar rivalry but in the structural logic of alignment itself. When the system’s continuity is at stake, states organize around necessity rather than principle. Moral language recedes, and the maintenance of systemic order, ensuring that networks, flows, and capacities continue to reproduce, becomes the decisive mode of political behaviour. This is why the question of blocs is not merely rhetorical. The carbondollar bloc is an alignment built around energy and money, and its rival is not a single state but a competing system of electrification and green infrastructure.

The coherence of this alignment becomes clearer when energy and money are treated as a single system. If the United States and the Gulf states form a carbondollar bloc, the rivalry is not only over currency but over the material logic that currency is meant to stabilize. The carbondollar bloc is not simply the petrodollar system; it is the broader architecture that converts fossil energy into monetary power and stabilizes global exchange in a carbon based order. In the language of contemporary energy history, this system is sustained through the continual management of supply and demand, the policing of access, and the institutionalisation of energy as a strategic commodity, a logic that has shaped modern geopolitics for decades (see Daniel Yergin’s The Prize). The alternative Tooze identifies is not merely a competing currency arrangement, but a rival system organized around electrification and green infrastructure, the networks and materials required for a decarbonised economy. The contest, therefore, is not simply about which unit of account prevails, but about which regime of production and reproduction becomes the organizing principle of global power. In this light, the lecture reads not as a menu of policy choices but as a diagnosis of systemic vulnerability.

Tooze further clarifies this vulnerability through a distinction between state forms shaped by their energy regimes. The carbonstate is organized around rents, contracts, and legal stabilization; it is governed by lawyers, financiers, and institutions designed to manage scarcity, volatility, and the politics of extraction. The electrostate, by contrast, is organized around engineering, grids, capacity planning, and scale. Authority here is exercised through technical coordination rather than juridical mediation. This distinction helps explain the paradoxical character of the present moment; extraordinary levels of intentionality coexist with persistent instability. States act with confidence, undertaking large scale infrastructure projects and territorial reorganization, even as they confront overlapping crises that resist resolution. Tooze characterizes this condition not as incoherence, but as a second modernity, in which modernizing logics persist under radically altered planetary constraints.

The lecture also draws explicitly on Hayden White’s insight that historical understanding is shaped by narrative form. Tooze suggests that contemporary energy transitions are being framed through divergent narrative genres. In the Western case, the story takes the form of a Comedy. Societies awaken to the planetary consequences of their energy systems, recognize that the Great Acceleration entailed profound ecological damage, and attempt to correct course through regulation, decarbonization, and institutional reform. Yet this awakening is accompanied by a persistent impulse to preserve the underlying carbon order through technological innovation. The carbonstate does not simply admit the climate crisis, if it does admit it; it seeks to manage it, often by reframing solutions as new forms of efficiency or new modes of extraction, as with the rise of fracking. The tone is therefore ironic and self critical; reform is imagined as repair rather than rupture, and innovation is presented as a way to maintain continuity under the guise of transformation.

China’s trajectory, as Tooze presents it, follows a different narrative logic. It resembles Romance in the classical sense; a story of struggle against poverty and underdevelopment. Coal and carbon powered that struggle with full awareness of its costs. Environmental destruction and mass mortality were understood as the price of development and political survival. What distinguishes this trajectory is not denial, but sequencing. Violent industrialization was followed by an equally forceful pivot, beginning in the 2010s, toward electrification, green infrastructure, and technological remediation. This turn was not moralistic but existential. For the Chinese state, technological transformation becomes a condition of regime survival.

A long durée perspective sharpens the contrast. When viewed across megageographies inhabited by millions of individuals, the spatial and demographic challenges faced by different polities diverge dramatically. North America operates across a small number of such geographies; China across nearly twenty. The difference is not merely one of scale, but of governance. Managing electrification, infrastructure, and decarbonization across such complexity requires a distinct relationship between state, technology, and population. What appears externally as hyper agency emerges internally as a response to geographic and demographic necessity.

The lecture also implies a transformation in the conditions of authority themselves, a transformation in which the reproduced becomes the site of legitimacy. In earlier technological revolutions, the act of reproduction diminished the singularity of objects, loosening their grip on legitimacy and the circuits of circulation. Today, the rupture is not in the copy but in the system. Energy networks, supply chains, and computational infrastructures do not merely replicate discrete goods; they reproduce capacity, stability, and power across space and time. Authority no longer resides in a unique site or a singular owner but in the capacity to sustain and direct these reproducing systems. Strategic advantage is therefore less about possession than orchestration, about the ability to govern the flows that make modern life possible. This is why the distinction between carbonstate and electrostate matters; the former seeks to preserve reproduction through legal and financial mechanisms, the latter through technical coordination and scale. Control over reproduction becomes the new locus of aura, in the sense of Walter Benjamin’s reflections on the loss of singularity, the point at which infrastructure, technology, and authority fuse into a single, distributed sovereignty.

Tooze’s contribution lies in the clarity of this diagnosis. He resists both nostalgic analogies and technological determinism, offering instead a framework in which energy, money, infrastructure, and narrative are understood as mutually constitutive. Power in the twenty first century is not disappearing; it is relocating into systems that are harder to see and harder to contest. The new architecture of power is being built in grids, supply chains, and infrastructures of reproduction. Tooze gives us a way to see that architecture without pretending that it can be easily mastered.