Bacchus and Ariadne was painted by Titian between 1520 and 1523 for Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, as part of a cycle of mythological paintings for the Camerini d’Alabastro, a series of small, private chambers designed to display the duke’s taste, erudition, and engagement with classical culture. The work depicts the moment Bacchus first sees Ariadne on the island of Naxos as told by Ovid and others, blending narrative drama with symbolic and seasonal references, including astrological markers that would have been legible to learned Renaissance viewers. Today it is housed in the National Gallery in London. This post is dedicated to Sergei Zotov (Frances Yates Fellow, Warburg Institute) who instructed a course titled Visual History of European Alchemy that I enjoyed immensely.

In the early modern imagination, wine was more than a fermented beverage; it was a substance of transformation, a medium through which celestial and terrestrial realms could intersect, and a vehicle for alchemists to apprehend hidden patterns in nature. The fifth essence, that luminous principle distilled from wine, promised vitality, illumination, and the fusion of matter and spirit. Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne, painted between 1520 and 1523, stages a mythic encounter suffused with this sense of transformation. The painting does not simply narrate a story; it performs an alchemical operation in light, pigment, and gesture, translating material into spirit through the formal language of Renaissance humanist painting.

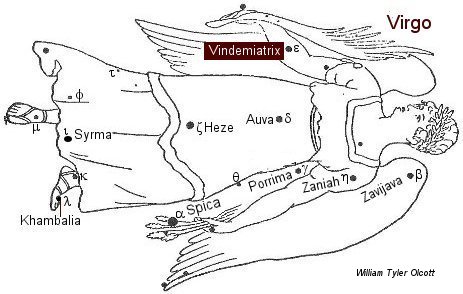

In this composition, Ariadne assumes a role resonant with the constellation Venus. She is luminous, elevated, and poised, a figure whose presence signals fertility, cosmic harmony, and generative force. Renaissance humanists frequently identified Ariadne with Venus in allegorical and poetic discourse, emphasizing her celestial elevation, her beauty, and her function as an agent of natural and human abundance. This identification is reinforced by the sources Titian consulted. Both Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Catullus’ 64 describe Ariadne’s abandonment and subsequent apotheosis into the constellation Corona Borealis. Her celestial transformation aligns her with the principles Venus embodies: the ordering of natural rhythms, the mediation of desire and abundance, and the harmonization of earthly and heavenly forces. In Titian’s painting, Ariadne’s raised right arm marks the heliacal rising of Vindemiatrix (Epsilon Virginis), signalling the beginning of the grape harvest. Her gesture connects the narrative to the cycles of the cosmos and the timing of human labour, situating her simultaneously within myth, season, and celestial order. This temporal tension between the springtime flora and the autumnal astronomical signal creates a poly-temporal tableau in which narrative, season, and cosmos intersect: Ariadne, like us all, is suspended between the life-time of flowering and the death-time of harvest, between growth and fruition, between mortal grief and celestial transformation.

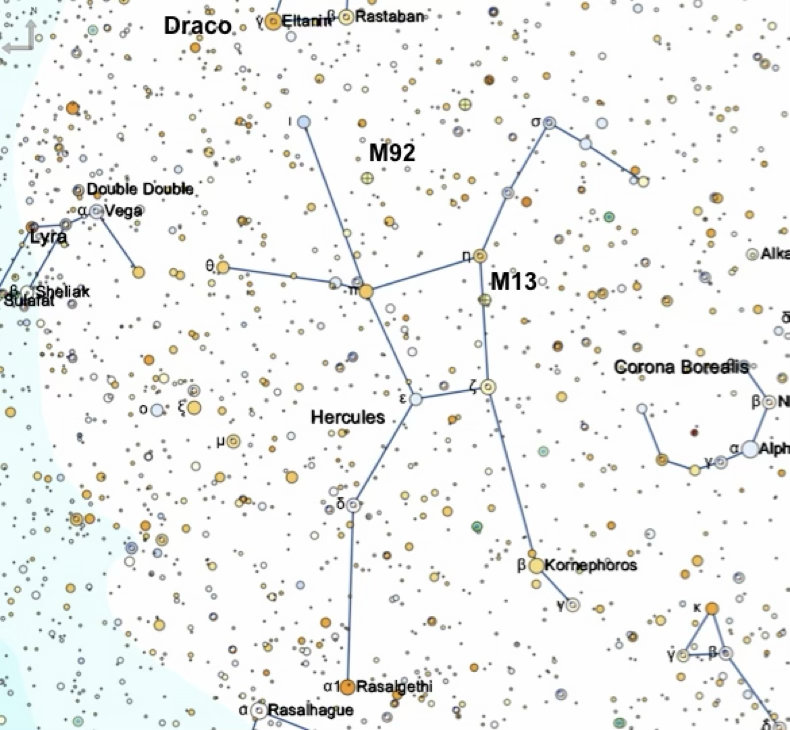

Bacchus is depicted as the constellation Hercules, leaping with muscular tension across the canvas. His leap is kinetic, cosmic, and narrative, connecting vineyard, myth, and sky. Hercules traditionally embodies struggle and ascension; Titian translates this into a corporeal movement that intersects with Ariadne’s stabilizing, Venus-like presence. The interaction of Bacchus and Ariadne is therefore not simply romantic; it is a moment in which cosmic, seasonal, and narrative energies converge, a visual analogue to the distillation of wine into its essential spirit.

Titian extends this cosmology into the Bacchic retinue, whose figures echo both mythic and celestial prototypes. Serpentus evokes the constellation Serpens, a visible celestial intermediary during harvest time, signaling transformation, danger, and the mediation between higher and lower realms. A small dog recalls the myth of Icarius, the shepherd of Attica who first learned the art of winemaking from Dionysus. When Icarius shared the fermented grape with his fellow shepherds, they mistook its intoxicating effects for poisoning and killed him; the dog, Maera, survived and led Icarius’ daughter Erigone to his body, marking the mythic origins of human engagement with wine. These figures link human action, natural processes, and celestial observation, embodying the duality inherent in wine and alchemy: vitality and revelation on one hand, peril and misinterpretation on the other.

Ovid, Metamorphoses 8. 175 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.) : "She [Ariadne], abandoned [by Theseus], in her grief and anger found comfort in Bacchus' [Dionysos'] arms. He took her crown and set it in the heavens to win her there a star's eternal glory [as the constellation Corona]; and the crown flew through the soft light air and, as it flew, its gems were turned to gleaming fires, and still shaped as a crown their place in heaven they take between the Kneeler [the constellation Hercules] and him who grasps the Snake."

The vegetation further reinforces the alchemical and cosmological logic. Vines, both crown and trailing, signal Bacchus’s domain and the medium through which celestial essence is communicated. Blue iris and columbine mark the late spring season, while Mediterranean caper and horsetail add botanical specificity, suggesting Titian’s careful observation of nature or consultation of botanical illustrations. Wild roses and woodland trees enrich the ecological tapestry, situating the figures in a fertile, transformative landscape. These plants are not merely decorative; they serve as witnesses to and participants in the processes of transformation, linking the narrative to earthly abundance, seasonal rhythm, and the hidden forces alchemists sought to extract from natural substances.

Colour and light function analogously to alchemy. Titian suspends pigment in oil to create surfaces that radiate from within, turning flesh, drapery, and landscape into luminous material that enacts transformation visually. The billowing fabrics, the glow of Ariadne’s blue mantle, and the vivid interplay of greens and golds mirror the extraction of quintessence from matter, providing a painterly analogue to the separation, condensation, and refinement characteristic of distillation.

Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara from 1505 to 1534, cultivated a court that was intensely invested in both the arts and intellectual experimentation, including interests that intersected with alchemical thought. While there is no evidence that he practiced alchemy personally, his court was closely connected with scholars and natural philosophers who engaged in the study of transformation, the properties of substances, and the hidden order of nature. The Camerino d’Alabastro, for which Bacchus and Ariadne was commissioned, functioned as a site of cultivated curiosity where myth, science, and art converged, and Alfonso’s patronage encouraged painters like Titian to explore complex correspondences between matter, light, and the cosmos. In this environment, the language of transformation inherent in alchemical theory in which the extraction of quintessence, the harmonization of elements, and the revelation of hidden structures would have been intelligible to the duke and his circle, making a painting such as Bacchus and Ariadne resonate not only mythically but philosophically and cosmologically.

Bacchus and Ariadne can be understood as an alchemical tableau in which myth, matter, and cosmos converge. Bacchus brings the fermenting vine and the energy of transformation, while Ariadne, Venus-like, receives and channels these forces; the retinue and surrounding flora encode celestial rhythms and seasonal knowledge. By juxtaposing springtime blooms with the autumnal timing of the grape harvest, Titian emphasizes that transformation is not fixed to a single moment but unfolds across overlapping registers of time—cosmic, terrestrial, and human. In rendering myth, nature, and the heavens in a single luminous scene, the painting enacts the very process alchemists pursued: the extraction of essence, the harmonization of opposites, and the revelation of hidden order. Titian does not merely depict wine; he distills it, making visible the intersection of human imagination, natural processes, and celestial patterns in a work that is both sensual and intellectually radiant.